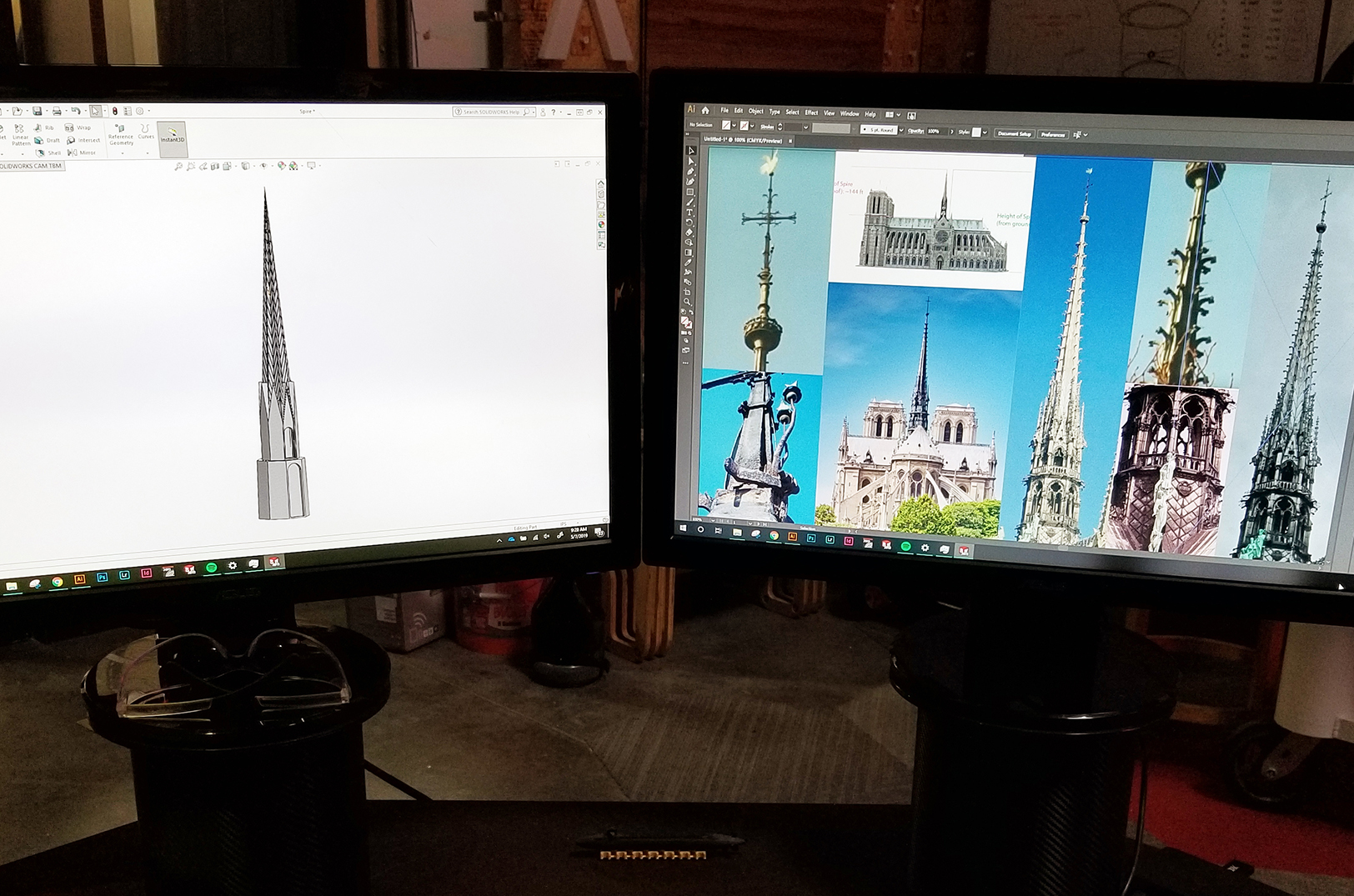

Beyond its status as the biggest in Kansas City, the impact of Dimensional Innovations’ new $2.2 million 3-D printer could reach globally — as the homegrown company considers ways it could help rebuild the historic spire atop the Notre Dame Cathedral, said Nate Borozinski.

“This thing gives us an ability — and we think an advantage — in the entire situation because it’s so versatile,” said Borozinski, Innovation Lab manager at the Overland Park firm who works closely with its large scale additive manufacturing machine known as L-SAM.

The device could closely replicate what was lost in the April fire that tore through the 856-year-old Parisian cathedral, he said.

“We’re not going so far as to say we’re going to redesign [the spire] at this point. We’re saying we can rebuild it in a way that was not there a few weeks ago and we can do it a lot faster than any other method … and it’s a way that less susceptible to fire,” said Borozinski, explaining Dimensional Innovations’ pitch for rebuilding the 300-foot spire through a competition sponsored by the French government.

Click here to learn more about the French call for designs in light of the destruction of Notre Dame.

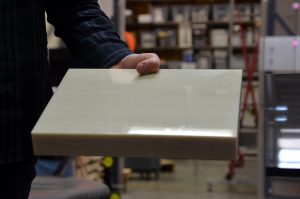

Large scale additive manufacturing machine ( L-SAM), Dimensional Innovations

“[A co-worker said,] ‘Hey, there’s a competition’ …. And it’s like ‘Yeah, we could do that now. Let’s do it,” Borozinski said of team collaboration and the initial idea behind dreaming up what could become a piece of history.

Purchased with the intent to advance Dimensional Innovations’ ongoing work in the design space — which already has included such projects as a life-sized Acrocanthosaurus at the Arizona Museum of Natural History, a complete overhaul of Target Center in Minnesota, and a 12-foot high, 500-pound electric guitar that welcomes guests to Kansas City’s Boulevardia — the L-SAM could also serve as a means to elevate the metro’s innovation space and open a door to new collaborations in 3-D printing, added Tom Collins, COO of Dimensional Innovations.

“Someone’s coming up with something new all the time. With both the spire and our other projects we’re looking at right now, what we’re thinking about in those worlds is [producing] more architectural elements,” Collins explained.

An under-wraps, large-scale element already is being constructed using the L-SAM, he acknowledged, noting only the project’s design and significance will bend people’s minds in new ways.

It’s about bridging digital and physical, Collins said, noting architecture represents not only a new market for the company, but an opportunity for rapid adoption of 3-D printing in commercial construction.

“We’re excited about partnerships with architecture firms, engineering firms, general contractors, — which are people that we work with but don’t necessarily partner with all the time. We’re excited about getting that community together in Kansas City,” Collins envisioned.

Using the L-SAM machine — which can produce items as massive as 10 feet wide, 20 feet long and 5 feet high — to produce construction materials could serve as a way of showing the world just how powerful 3-D printing can be, helping them better understand its potential, Collins said.

“I think the spire is a good example … because people traditionally don’t think about things like that being printed, right? When you can take that theory and make it something that is a real physical daily [object] then you can [better understand the importance of 3-D printing and how it works,” he said.

Click here to read about Doob 3-D’s challenges in the Kansas City 3-D printing space.

Working to create more examples of the power behind 3-D printing could prove to be just what the technology needs for widespread adoption, Collins said.

The opportunity to do so on a global scale with the rebuild of Notre Dame could convert even more curious citizens into customers, he noted.