Editor’s note: The Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City (EDCKC) and KC BizCare are partners of Startland News.

Kansas City is betting that a global microlending model — one built on $25 contributions and community belief in everyday entrepreneurs — can help close one of the city’s most stubborn gaps: early-stage capital for founders who are new, unproven or traditionally shut out of bank financing.

Kiva, the international nonprofit best known for fueling small enterprises overseas, operates a domestic arm through local “hubs,” with Kansas City among them. (The local initiative is administered through the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City (EDKC) with support from KC BizCare.)

The premise is refreshingly simple for entrepreneurs: They can raise zero-interest microloans on Kiva’s platform, and local partners step in to accelerate the process. In Kansas City’s case, that includes 4-to-1 match funding from the city, hands-on coaching and a deliberate push to reach founders who have learned to expect “no” from lenders long before they ever hear “yes.”

The early numbers are small — but meaningful.

Since the program launched in 2024, 15 loans totaling $111,000 have moved through the Kiva Kansas City pipeline. The average loan size sits at $7,400. The average time to fund is just 15 days.

Additionally, the borrower mix makes the city’s intent unmistakable: 80 percent of recipients fall into Kiva’s Tier 2 category, meaning they have limited access to traditional financing. Another 13 percent are Tier 3 borrowers, the most marginalized in Kiva’s system. Only 7 percent come from the most bankable Tier 1.

Kansas City, in other words, isn’t subsidizing entrepreneurs who already have options. It’s testing a model designed for people who don’t.

Kiva’s global ecosystem adds weight to KC’s early gains

Kansas City’s progress sits inside the larger, well-established Kiva network. According to Kiva’s 2024 Annual Report, the organization’s global lending community:

- Funded 202,875 loans internationally in 2024;

- Reached 315,867 women entrepreneurs, with 79 percent of loans flowing to under-banked women, totaling $109,904,638;

- In the U.S., directed 3 out of 4 loans to BIPOC-owned businesses, supporting 2,357 borrowers with more than $7.5 million in domestic microloans;

- Reports — through independent surveying — that 89 percent of borrowers say their lives are better overall because of their Kiva loan; and

- Operates on a model where 100 percent of lender dollars go directly to borrowers, not administrative overhead.

For Kansas City, that credibility matters, Regina Sosa, capital access manager at the EDCKC. The hub is young, small and still earning trust, she noted, so skepticism is baked into the process.

“The feedback I get a lot is, ‘This is too good to be true. Zero percent interest? Where’s the catch?’” said Sosa. “A lot of my work is just educating entrepreneurs and partners on how the model really works.”

Kiva’s global scale doesn’t guarantee local success. But it does lend weight to Kansas City’s early signals — and it reassures first-time borrowers that they aren’t stepping into a funding gimmick.

Regina Sosa, EDCKC, speaks in September about the KIVA KC initiative during a Lunch and Learn session at City Hall; photo by Tommy Felts, Startland News

A model built for people who need it

Kiva’s structure is intentionally different from conventional small-business lending. There is no credit score threshold. No collateral requirement. No multi-year financial history needed.

“Kiva is an international nonprofit,” Sosa said. “They started in the early 2000s helping farmers overseas. After that success, they wanted to bring the concept home.”

Kiva U.S. launched in 2011. Kansas City became an official hub in 2024.

“Kiva U.S. trains these capital access managers — so, me — on how to talk about the Kiva loan product, how to identify good candidates and how to conduct the pre-underwriting,” Sosa said. “I like to describe it as me being the middleman between Kiva U.S. and the applicant.”

Kansas City entered the partnership with a clear objective: carve out an accessible alternative for founders who are too early, too new or too underestimated to walk into a bank and walk out with working capital.

“Banks typically want three-plus years of financials,” Sosa said. “But what if you’re new — or testing an idea? Kiva loans can start at $1,000. They let founders try things out.”

Multiple matches

Applications for Kiva loans are open year-round — and Kansas City’s hub stays open even when Kiva U.S. pauses applications elsewhere to clear backlogs. That’s already a competitive advantage.

But the matching structure is what sets KC apart, and Sosa spells it out clearly.

“What that means is that there is an organization or sponsor who has set up a matching fund on Kiva,” she said. “For Kansas City, the city put up about $100,000. For every $25 a supporter lends, the city contributes four times that — $100.”

This doesn’t inflate the borrower’s debt. It just accelerates the path to funding. Supporters contribute $25; the loan dashboard jumps by $125. Additionally, Kiva U.S. has added another layer of matching funding through a grant from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation earmarked specifically for the KC metro, one that creates a 2-to-1 match while those funds last.

Fast fundraising matters. Many early-stage founders don’t have weeks to wait for capital — they need inventory this week, childcare this week, a website this week, a pop-up booth this week. The match turns growth capital sourcing into a sprint instead of a slog.

Underwriting for the human, not the balance sheet

While the match program draws headlines, Kiva’s real innovation sits in its underwriting philosophy.

“Kiva is very impact-driven,” Sosa said. “In the application, we want to know about the person behind the business even more than the financials.”

Founders submit a personal story, a business story and a clear articulation of impact. That requirement, Sosa argues, is not a feel-good feature. It’s a guardrail. It helps Kiva identify founders who know their “why,” not just their numbers.

“Everyone interested in a Kiva loan should know exactly what they’re getting into,” she said. “The crowdfunding part shouldn’t be a surprise. The terms shouldn’t be a surprise. That’s the conversation we have prior to them applying.”

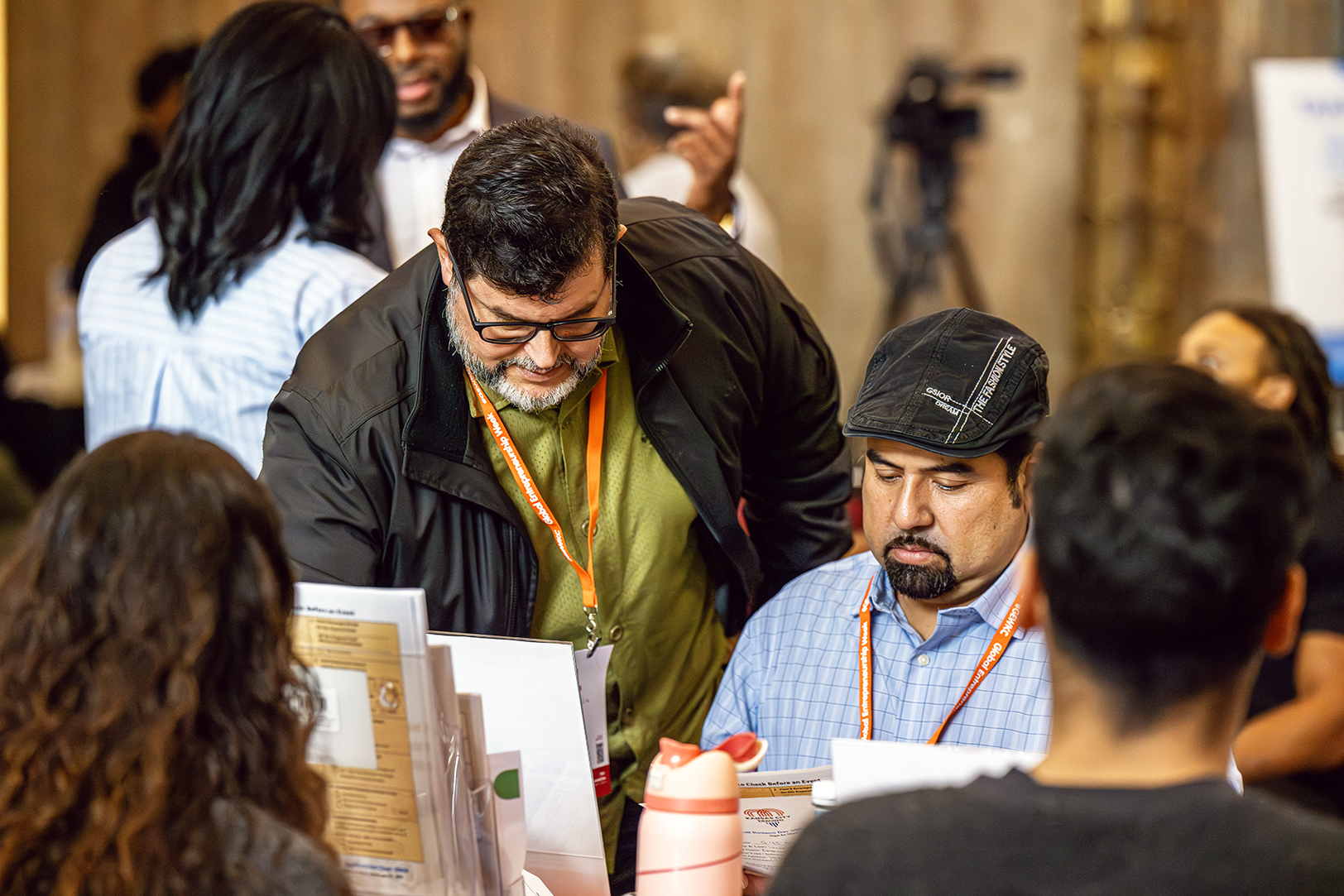

Entrepreneurs visit with Regina Sosa, EDCKC, and representatives from the KC BizCare Office during November’s Small Business Day at City Hall; photo courtesy of the KC BizCare Office

KC’s trustee network: The force multiplier behind the loans

Kiva’s trustee program adds another relational layer that Kansas City has leaned into quickly. Trustees — often nonprofits, chambers, or service providers — identify entrepreneurs who are ready for Kiva and make warm referrals into the program.

Here, Kansas City has already built partnerships with groups including the Heartland Black Chamber of Commerce, Pathway Financial Education and Black Excellence KC.

“What’s really great about the trustee program is that trustees have no financial obligation,” Sosa said. “If someone they endorse gets a loan and then can’t repay it, the trustee doesn’t have to cover that.”

Still, trustees get something valuable: a dashboard showing exactly how many entrepreneurs they’ve helped and how much capital those businesses have captured. In a city where ecosystem players often work in silos, that visibility matters.

A chemist/professor ‘Kivas’ into community-building entrepreneurship

If you want to see what a Kiva loan looks like in practice, talk to Antwan Daniels — chemist, educator, community researcher and founder of Five S Scientific Solutions in Kansas City’s Third District.

“Kiva was my hockey stick,” Daniels said. “I was already moving, but they were my inflection point going up.”

His background spans high school science teaching, college chemistry instruction, advisory work, STEM literacy research and grant writing. Five S blends all of that into three pillars: STEM advocacy, advisory services and the increasingly popular “Cool Kids Chemistry” program.

The Kiva loan helped Daniels do something simple but rare: pause the survival grind.

“You can think a little bit,” he said. “You’re not in the weeds. You can look and plan.”

He used his $2,500 loan — repaid at 0 percent interest — to upgrade his website, develop content, support staff and stabilize operations. The return was immediate.

“I took $2,500 and turned it into about $7,700 of new contracts or upsell services.”

Those contracts included Kansas City Public Schools, Boys and Girls Clubs and Upper Room KC.

Daniels’ long-term plan is even more ambitious: STEM box kits for fourth- and fifth-grade students, a push to move below-proficiency math scores on the Missouri side of Kansas City and eventually a regional scale model he half-jokingly calls “the I-35 Look Alive.”

His vision is grounded, not dreamy — and the Kiva loan gave him momentum rather than miracles.

“The money isn’t in the profit,” he said. “The money’s in the people. You bring more good darn people, I’ll make more GDP — good darn people.”

Microloans, not miracles — but a heck of a start

Daniels sees Kiva clearly: not as charity, and not as a lottery ticket.

“Kiva didn’t hand me anything,” he said. “They gave me a chance to prove what I was already doing could work.”

Sosa echoed that sentiment.

“We’re still early,” she said. “But every success story shows Kansas City is full of entrepreneurs who just needed that first push. Kiva lets the community be that push.”

The program will need more trust, more awareness, more trustees and more first-time borrowers willing to take a risk on themselves, Sosa said, but with 15 early loans — most to founders who banks routinely overlook — the foundation is set.

Haines Eason is the owner of startup content marketing agency Freelance Kansas. Previously he worked as a managing editor for a corporate content marketing team and as a communications professional at KU. His work has appeared in publications like The Guardian, Eater and KANSAS! Magazine among others. Learn about him and Freelance Kansas on LinkedIn.