Editor’s note: The following is the second in a four-part series exploring the verticals and impact of initiatives within the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City through a paid partnership with EDCKC.

- Leave KC better than you found it: How matching growth to city’s needs is paying off

- Homegrown startups can redefine KC; they just need help surviving long enough to do it

- Feel good, but get off the bench: KC’s next big wins require all players join EDCKC in the field

Ensuring a vibrant future for Kansas City’s broad mix of residents requires a block-by-block approach, said Dan Moye, emphasizing that redevelopment efforts must engage impacted community members from the jump.

Their input and buy-in is critical for lasting growth, explained the vice president of land development for the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City, Missouri (EDCKC), noting leaders can’t just toss dollars at a project and then abandon it, leaving an island of impact that ultimately dwindles back to nothing.

“If you’re not building up support around it — creating a thriving community — you’re going to end up in the same place five or 10 years later,” said Moye, who steers EDCKC’s efforts to implement the city’s incentives process through policy work, scrutinizing potential deals, and communication between developers and impacted residents, businesses and other entities.

An example of development gone right: the Linwood shopping center, he said.

Built about 10 years ago in an underinvested area, the vacant structure fell within a food desert, Moye recalled.

“The city was very targeted in how they approached the project, and it has led to spillover development across the street and to the other shopping centers along that area with more money going back into that community,” he said. “Now, it’s also an example of how just throwing money at things is not always the answer — because that shopping center continues to need assistance. And we’re continuing to work with them, but it’s a start.”

Empowering, preserving neighbors

The next step requires investing in neighborhoods themselves, Moye said.

“Residents and business owners know what they need and what they want to do,” he explained, “and frequently, they know who they want to do it with.”

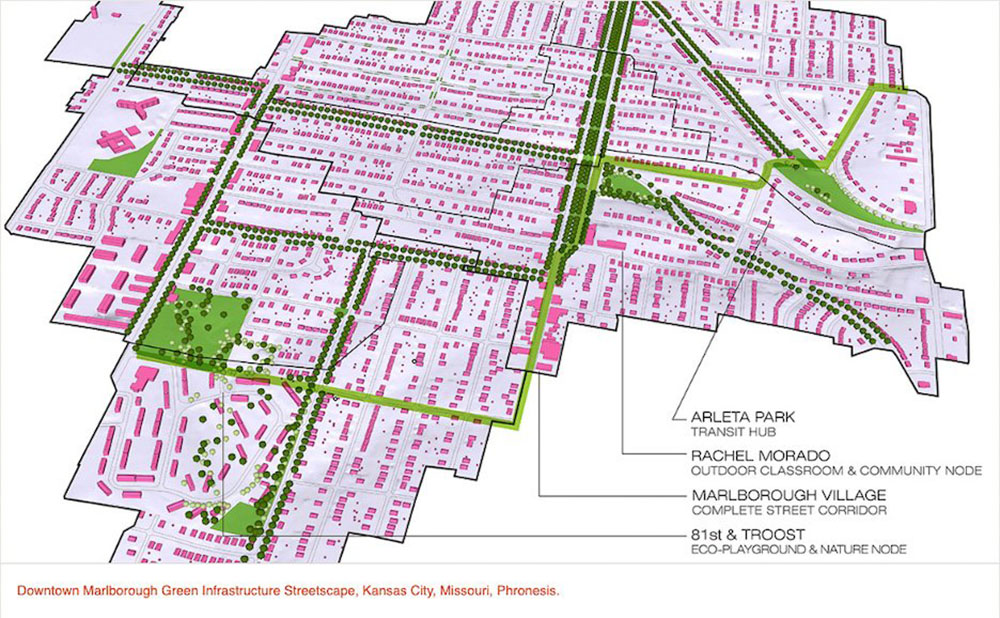

The Marlborough neighborhood — an area in the southeast bordered by Gregory Boulevard to 89th Street, and from Troost to Highway 71 — is worth noting, he said. The neighborhood is the regional leader in community land trusts, which it has used to redevelop a local school and create affordable housing.

“They’re starting to set up models that are truly benefiting their neighborhood and their neighborhood gets to participate in it,” Moye added. “So I think that’s a really interesting model, as well.”

Urban renewal and community needs are not mutually exclusive, he stressed.

“This is not unique to Kansas City, but when you’re developing any historically underinvested area, the concern is gentrification,” he continued. “So we have to help take steps to preserve — I don’t know that the word exists, but — ‘good gentrification.’”

This means helping the neighborhoods become more diverse from a socioeconomic standpoint, he explained, but protecting those people who are already living in the area by creating programs that help people stay in their homes and age in place.

“Historically, the East Kansas City Urban Renewal Area was an example of a step that we’re trying to take to do that,” Moye added, “because if a homeowner invests $5,000 into their home in areas of the East side, they can freeze their property taxes for 10 years.”

So what’s in the toolbox?

The EDCKC land development team is at its best, Moye said, when it walks and chews gum at the same time. They can’t just focus on one type of development, like downtown skyscrapers, sprawling data centers, or affordable housing, and expect holistic or widespread positive impacts.

Steven Anthony, Tracey Lewis, and Dan Moye, EDCKC, at the Google announcement event in March 2024; photo courtesy of the EDCKC

“We have the ability to act in different areas,” he explained. “It’s incumbent on us to help attract folks who are willing to cross into multiple lanes — to find the folks interested in developing Kansas City from all sides.”

The team uses tools like Tax Increment Financing (TIFs) and tax abatements, he noted.

Tax abatements go by many names — an alphabet soup, as he called it — like LCRA (Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority), PIEA (Planned Industrial Expansion Authority), and 353 (Chapter 353 Program). They all abate taxes for a period of time. With a TIF, it’s a redirection of taxes.

“Historically, there’s been a big challenge in that communities have wanted the city to use TIF more judiciously in different communities,” Moye explained. “The challenge there is that — if we’re looking at a toolbox — TIF is a sledgehammer. It is designed for large projects because it’s designed to be redirected. It’s a delayed tool. So it makes sense for projects that have a lot of cash in them and a lot of things going on.”

For smaller projects, developers typically are looking for ways to avoid paying at all, he noted.

“Because then that money can just go into their other operations,” Moye continued. “So it’s always been important for us to be able to clearly articulate why different programs work in different areas, projects and developers.”

Industrial Development Authority (IDA) also can help with financing, he said.

“They’re able to issue tax exempt bonds and do things that set up the infrastructure of a project,” Moye explained. “Those are not direct tax incentives, but just another tool to help projects succeed.”

Click here to learn more about EDCKC and how it can help.

Dan Moye, vice president of land development for the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City, at EDCKC’s offices in River Market; photo by Taylor Wilmore, Startland News

Project fit matters

It’s a matter of tying the right tool to the right project and explaining to stakeholders how pursuing the correct option can make or break a plan for development, he added.

“If you’re wanting to put a bodega in your neighborhood, we’re going to want to direct you one way because we can make it quick for you,” Moye explained. “We can make it easier.”

For example, through LCRA — which focuses on redevelopment within designated urban renewal areas like 40 acres on Kansas City’s East side — if an applicant meets certain criteria, such as being owner occupied or affordable housing, they are directly sent to City Council for approval. If not, then they must obtain a letter of approval from the neighborhood before moving forward.

“We’ve worked to identify those solutions that work for these communities,” Moye added. “We designed them to be inclusive of the neighborhoods, because we still want to listen to what they need and what they want.”

Historically, some residents have felt land developers have been too free to build whatever they want in neighborhoods — with too few restrictions placed on them, he said, acknowledging that ease of development is part of the design and an ongoing challenge faced by his team.

“Of course, we only want to bring forward proposals that should truly be approved,” Moye continued. “If a plan for a development isn’t good, if it’s not been reviewed, if it’s lacking its due diligence, we’re not going to put it in front of a board for approval.”

“That means if it doesn’t check the boxes for the neighborhood, we’re prepared to send it back to square one.”