Editor’s note: The following story was published by KCUR, Kansas City’s NPR member station, and a fellow member of the KC Media Collective. Click here to read the original story or here to sign up for KCUR’s email newsletter.

Ivan McClellan’s new photobook, “Eight Seconds,” documents the Black riders, ropers and rodeo queens encountered in dusty arenas around the United States; McClellan’s love for the sport and subculture led him to start his own rodeo

PORTLAND, Oregon — Ivan McClellan once had a comfortable career in advertising and design. The Kansas City, Kansas, native worked on national campaigns for the U.S. National Soccer Team, Nike and Adidas.

For him, photography was just a hobby. But a chance encounter in 2015 with a filmmaker named Charles Perry would change the course of his life.

“I met him at a bar and we got to talking, and he said that he was working on a documentary about Black cowboys,” McClellan said. “I kind of laughed because the only image of a Black cowboy that I had in my head was Sheriff Bart in ‘Blazing Saddles.’”

Surely, McClellan thought, if Black cowboys existed, he would have heard about them.

“I just thought, that’s just sort of like a punch line and he said, ‘Come with me to an all-Black rodeo in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, this summer,’” McClellan said. “I had no idea it existed.”

Almost a decade and thousands of photographs later, McClellan has released a book on the subculture. “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture” rolled out on April 30. In it are photographs of the riders, ropers and rodeo queens he’s met in dusty arenas around the country.

“Handoff, Okmulgee, Oklahoma,” from Ivan McClellan’s new book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

McClellan didn’t know what he was getting himself into when he stepped out of his rental car on that first scorching summer day in Okmulgee, about 40 minutes south of Tulsa.

He’d taken Perry’s advice and was there to check out the Roy Leblanc Okmulgee Invitational Rodeo. It’s the nation’s oldest African American rodeo, and referred to by some as the Super Bowl of Black rodeos.

“I saw thousands of Black folks riding horses,” McClellan said. “Some of them were in traditional Western wear, and there were men with shirts so starched that they crunched when they moved their arms, sharp Stetsons, pinky rings and trimmed mustaches.”

A few of the riders were shirtless with gold chains, basketball shorts and Air Jordans. He saw women with braids billowing behind them and long acrylic nails clutching the reins while riding 50 miles an hour around barrels.

“It felt really foreign and surprising, but it also felt pretty familiar,” McClellan said. “It felt like the church that I grew up in Kansas City. It felt like hip-hop culture, but really mixed with the West in a way that was completely unexpected.”

“Jadayia Kursh, Okmulgee, Oklahoma,” from Ivan McClellan’s book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

McClellan grew up on a five-acre plot of land at 57th Street and Georgia Avenue, in Kansas City, Kansas. He watched reruns of television shows like “Bonanza” and “Gunsmoke.” He and his sister spent summers picking blackberries, climbing trees and catching fireflies in the field behind their home.

“This was really great, country living,” he said. “I think about the smell of wild onions and the Canadian thistle that would stick in your socks when you ran home.”

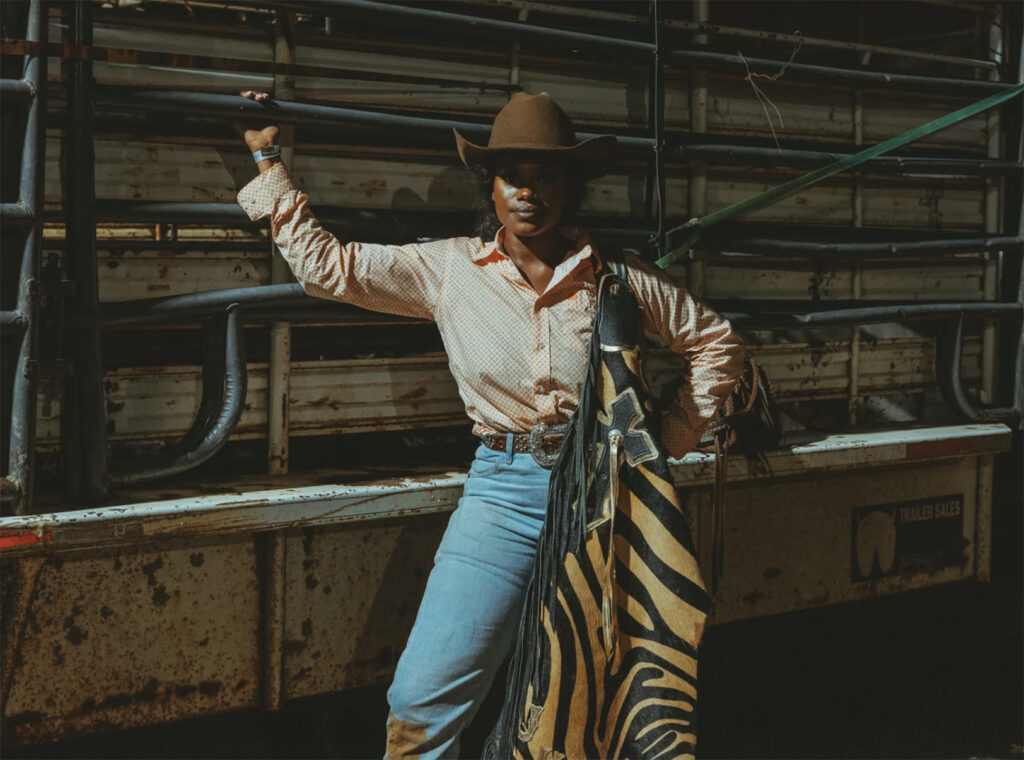

“Keary Hines, Prairie View, Texas,” from Ivan McClellan’s book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

Black riders, ropers, and wranglers played an integral role in the American West, but McClellan said he never heard about them growing up.

According to the Bureau of Land Management, one out of every four cowboys were Black.

“The Buffalo Bill Cody Wild West Show that traveled the world and set the conventions that the white man was the good guy, the Indian was the bad guy,” McClellan said. “Black people might have been around but weren’t consequential in the West, and Hollywood just sort of picked up all of those things and ran with them.”

At that first rodeo, McClellan met a man named Robert Criff.

“He just had these really rough, like, 12-grit sandpaper hands, and was wearing a Kansas City Royals hat,” he remembered. “Turns out Robert Criff lived less than a quarter-mile away from my childhood home and had horses and was a’cowboyin’ back there. He’s got a riding club and teaches kids how to ride.”

Criff also said many of the people at the rodeo travel from Kansas City every year for family reunions. McClellan was stunned.

“For me, not knowing about this rodeo, not knowing about this culture, a few paces away from my house, was embarrassing,” McClellan said. “It was also like a transformative moment that — not only do Black cowboys exist, but they are part of my culture, part of my neighborhood, part of where I grew up.”

“It changed my definition of home from a place of pain and poverty to a place of pride, grit, and independence,” he said.

“Rodeo Queen, Okmulgee, Oklahoma,” from Ivan McClellan’s book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

Since then, McClellan has spent close to a decade traveling around the country, immersing himself in the culture. He learned to rope and ride a horse.

McClellan started posting his images on Instagram and now has more than 25,0000 followers.

He’s been invited into athletes’ trailers and homes, and has seen firsthand the challenges Black rodeo athletes faced, physical and financial.

One of his best friends was a cowboy named Ouncie Mitchell. When McClellan met him, the bull rider was recovering from a broken femur.

“He missed the whole season and he’s barely getting by,” McClellan said. “But he was telling me, ‘I’m going to win the world championship in bull riding.’”

McClellan was skeptical, but Mitchell made a comeback. He had no financial backing and funded his season out of his own pocket. Before long, he started working his way up the rankings.

But Mitchell’s career was cut short in September 2022 when the woman he was staying with shot him to death.

“Dontez and Floss, Okmulgee, Oklahoma,” from Ivan McClellan’s book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

“It was the moment that I realized that I’m not just shooting photos. I’ve really gotten deeply involved in this culture and I’m part of it now,” McClellan said. “There’s no way to get out of it because my heart broke.”

To try to make the sport more sustainable, McClellan decided to start his own rodeo in Portland, Oregon, where cowboys could earn real prize money. He chose to hold it on Junteenth, the national holiday established to commemorate the end of slavery.

“Let’s give out big money and let’s help make it easier for these folks to get down the road, and make it so that situation doesn’t happen to the next guy,” he said.

Using his advertising experience, McClellan reached out to iconic western brands like Stetson and Wrangler, leveraging all his skills to change the way brands present themselves online, and bring more diversity to their advertising.

Now in its second year, the 8 Seconds Juneteenth Rodeo kicks off June 16, at Portland’s Veterans Memorial Coliseum. The event has helped bring the story of Black cowboys to a national audience, McClellan said.

“Audience, plus brands, plus cowboys equals rodeo,” he said. “Just put all those things together in a live space and you’ve got yourself an event.”

“Marland Burke, Brandon Alexander, James Pickens Jr. Los Angeles, California,” from Ivan McClellan’s book “Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture”; photo courtesy of Ivan Mcclellan, Damiani Books, 2024

The prize money is $60,000 across five events. Men and women are paid equally for their events. It turns out to be about $12,000 per event.

“That’s as much money as you get at the big pro rodeos, across multiple days and nine or 10 events, and way more money than you get at a typical Black rodeo,” McClellan said.

Offering real prize money that first year made a difference to the competitors.

“People bought horse trailers with that money,” McClellan said. “People stayed on the rodeo circuit longer and were able to get hotels and get good meals on the road.”

The money also helped rodeo clowns earn their pro card, so they were able to compete in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association.

“I think my theory about infusing this culture with capital is working,” McClellan said. “It’s not about talent, it’s really about having the funds to compete at a high level.”

McClellan said it’s also a chance for folks from around the country to gather, celebrate the Juneteenth holiday and be thrilled by Western sports.