Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Kansas City PBS/Flatland, a member of the KC Media Collective, which also includes Startland News, KCUR 89.3, American Public Square, The Kansas City Beacon, and Missouri Business Alert.

Click here to read the original story.

On June 27, 1967, Jackson County voters approved a $102 million general obligation bond package.

The money financed a new Kansas City hospital, flood control upgrades along the Little Blue River, and road improvements in rural and suburban parts of the county.

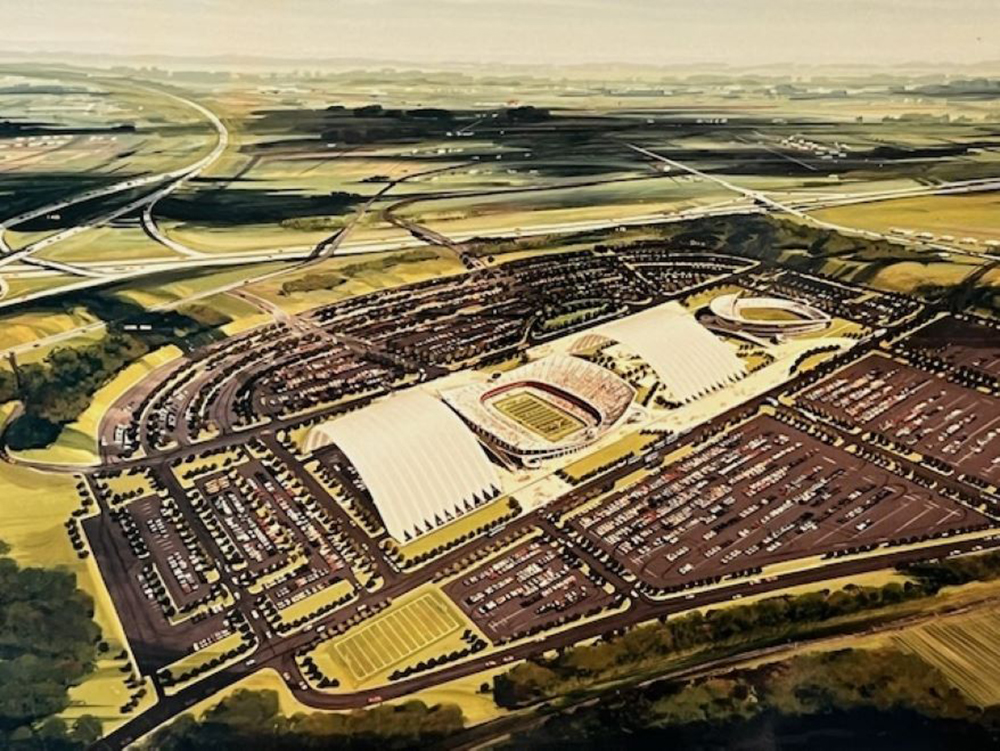

The package’s big-ticket item – then priced at $43 million, or about $400 million in current dollars – became the Truman Sports Complex.

The unique, twin-stadium Truman Sports Complex – designed to accommodate a dramatic rolling roof – was built on 384 largely vacant acres in Kansas City’s Leeds district, some eight miles east of downtown. The rolling roof was never built.

Almost forgotten in the decades since is that Kansas City seriously considered building a domed downtown stadium for both baseball and football. And that stadium would have been built in the Crossroads, just three blocks west of where the Kansas City Royals now want to build a new ballpark.

History may be rhyming, if not repeating.

A view looking west from the proposed Kansas City Royals ballpark that includes a proposed park atop the south side of the downtown freeway loop; Rendering courtesy of Populous

At a Crossroads

More than 90,000 voters – 36% of all residents registered – braved a tornado watch during the latter hours of Election Day in 1967 to vote on what The Kansas City Times dubbed “the most ambitious capital improvements bond program in the history of Jackson County.”

They spoke clearly.

Each proposition needed two-thirds, or 66.7%, approval. Each one passed, some by four-to-one margins, such as the new Kansas City hospital.

As for the not-necessarily-next-door sports complex, Kansas City voters supported the package in all 25 wards.

An editorial in The Kansas City Star celebrated the outcome the following day.

“A new General Hospital on Hospital Hill,” it read. “New roads, thousands of acres of parks, flood control on the Little Blue and two new stadiums.

“It is now definite that the Chiefs will continue to wear Kansas City jerseys.”

Dutton Brookfield, president of Unitog, a Kansas City uniform manufacturing firm, and Jackson County Sports Authority chair, basked in a shower of praise.

“You did it, coach,” read a telegram from Chicago, today filed in Brookfield’s papers, kept by the State Historical Society of Missouri.

But if the stadium vote was a victory, the margin was the political equivalent of a game-winning field goal that had clanked off an upright before brushing over the crossbar.

Proposition One, the sports complex proposal, received 69% approval across the county – a clear victory, but nowhere near the mandate the new hospital had received with 81% approval.

In Fort Osage township, in northeast Jackson County, voters opposed the sports complex proposal, with the nays representing 57% of the vote.

Voters in some Kansas City districts were clearly divided, with northeast Kansas City’s 12th Ward approving by only a 1,326-to-1,312 margin, or 50.26%.

Meanwhile, the Election Day tornado watch had proven apt. There had been cloudy skies aplenty leading up to the vote, with no shortage of discouraging words regarding the Leeds location, expressed both publicly and otherwise.

Those can be found in the Brookfield papers, too.

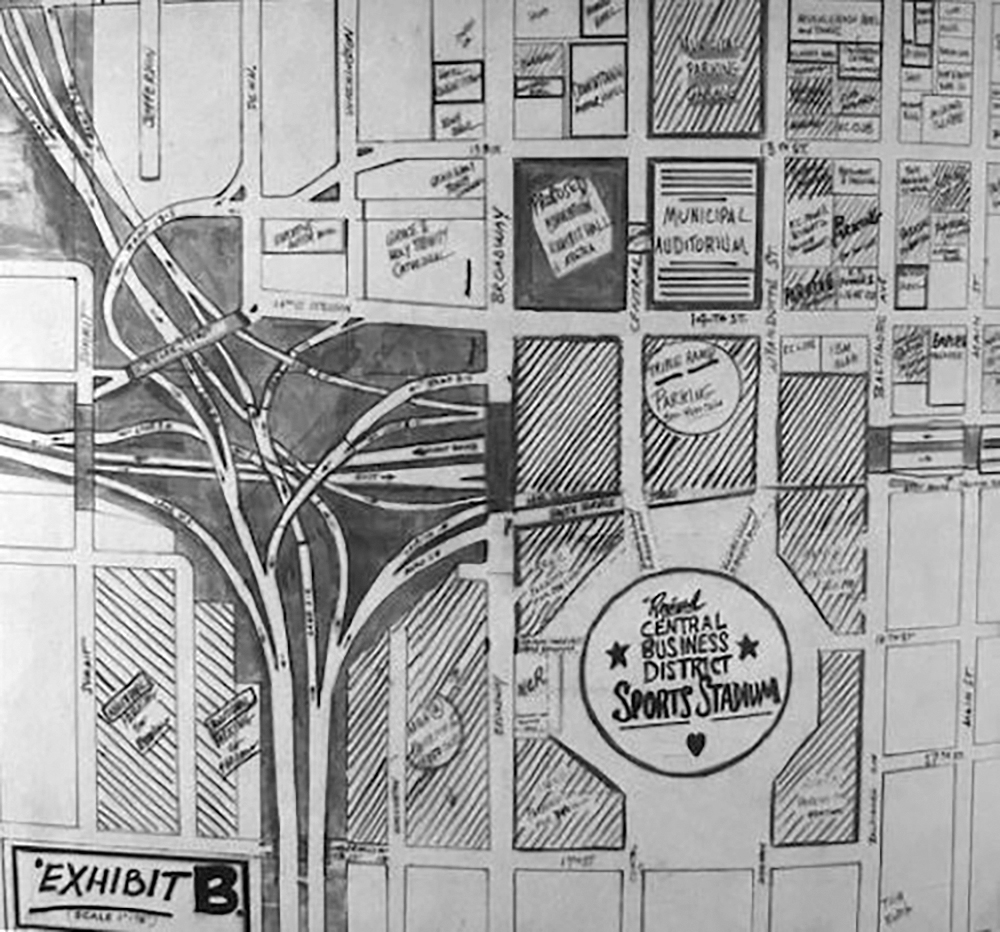

The Hotel and Motel Association of Greater Kansas City published a detailed breakdown of the wisdom of a central business district stadium.

Its preferred location was the current site of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, just east of Broadway at 17th Street.

In 1965 the Hotel and Motel Association of Kansas City announced its members believed a new stadium should be built just east of Broadway at 17th Street, the current location of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts; image courtesy of the Dutton Brookfield Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri

Any stadium location not downtown would be “highly unsatisfactory,” President Helmut Vogel declared in the organization’s November 1965 report.

In January 1967, the sports authority announced it would instead place the two-stadium Leeds proposal before voters.

That prompted lumber company executive Frank Paxton Jr., in a letter to Kansas City Mayor Ilus Davis, to insist “Kansas City’s civic-minded businessmen cannot be expected to subsidize a baseball fiasco at Leeds.”

Paxton added it was “imperative” that “Kansas City’s downtown area become something more than a nocturnal graveyard…filled with empty parking lots.”

Others had bristled at the proposed price tag.

Nat Fritz, a frequent contributor to the Star’s letters page, noted how a new 50,000-seat Memphis football stadium had been built for $3.6 million, compared to the approximately $25 million the sports authority was asking for the 75,000-seat football stadium at Leeds.

“Kansas City capitalists think big when the taxpayer is footing the bill,” Fritz wrote, sending a copy to Brookfield with an additional serving of snark.

”It seemed to me this was newsworthy – perhaps not,” Fritz added in a handwritten postscript on his message to Brookfield.

History of stadium angst

If Jackson County voters feel conflicted about the April 2 stadium sales tax vote to help finance a new downtown ballpark for the Royals and Arrowhead Stadium improvements for the Chiefs, they can be confident in this – angst over stadiums is a local tradition that goes back at least 93 years.

In 1931, Kansas City voters approved by a four-to-one margin a sweeping public improvements package known as the Ten-Year Plan that included $750,000 for a new outdoor stadium.

While several smaller venues had hosted various Kansas City teams beginning in the late 19th century, the modern era of Kansas City stadiums had begun in 1923 with the opening of Muehlebach Field at 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue.

That venue hosted the minor league Kansas City Blues as well as the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs, as well as Kansas City’s first pro football franchise in 1924.

But by 1938 a new stadium had yet to be built. A Star survey that year described such a facility as one of two “least urgent” needs in Kansas City.

The other was a municipal garbage incinerator.

In 1945, the Kansas City Plan Commission proposed two possible sites for a football stadium, one at the former site of Electric Park near 45th Street and the Paseo, the other at 45th and Cleveland Avenue.

The city built neither, as the first site later was developed for an apartment complex while homeowners near the second protested, fearing declining property values.

In 1954, the promise of the major league Philadelphia Athletics moving to Kansas City prompted swift action, as more than 78% of Kansas City voters approved a $2 million bond proposal to acquire and upgrade the Brooklyn Avenue ballpark, then known as Blues Stadium.

Workers added a second deck and the Athletics debuted at the new Municipal Stadium the following spring, with former president Harry Truman throwing out the first pitch.

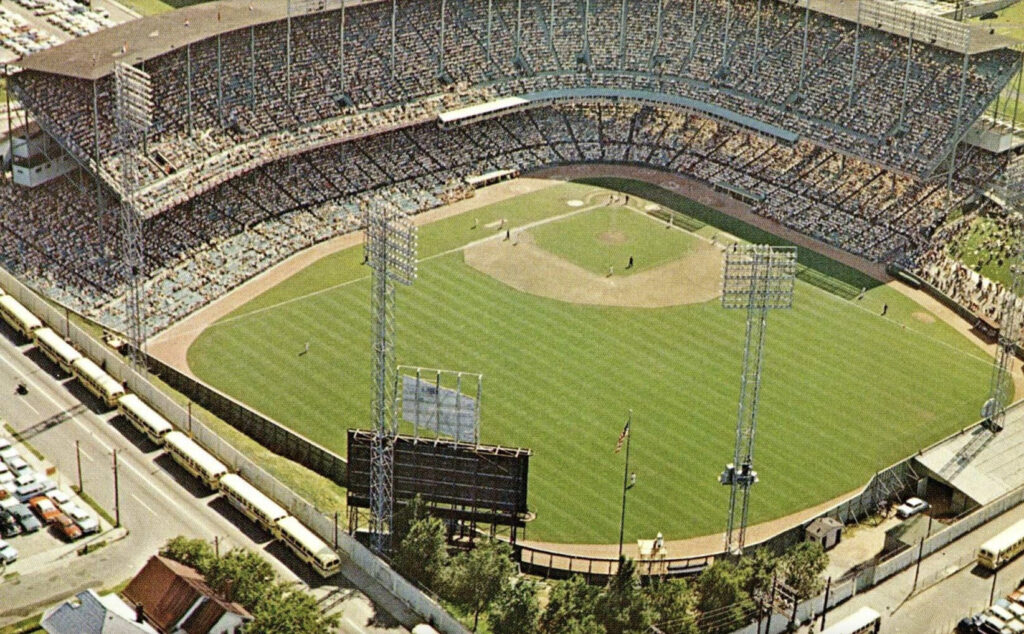

Kansas City Municipal Stadium in 1969, when the Kansas City Royals debuted; photo courtesy of Ballpark Digest

In 1963, the arrival of the American Football League’s Dallas Texans – renamed the Chiefs – brought top-tier pro football back to Kansas City after an almost 40-year absence.

But the future of both Kansas City major league teams often seemed in doubt, with Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt sometimes battling rumors that he was considering moving the team elsewhere, and Athletics owner Charlie Finley routinely alienating fans and city leaders about his own intentions.

By then the task of building a new stadium complex had proven too heavy a lift for just Kansas City.

Moving out

In November 1966, Jackson County voters re-elected presiding judge Charles E. Curry and chose Charles Wheeler and Alex Petrovic as western and eastern county judges, respectively.

All three had run under the “Committee for County Progress” slate, and all three would support the 1967 twin-stadium complex bond proposition.

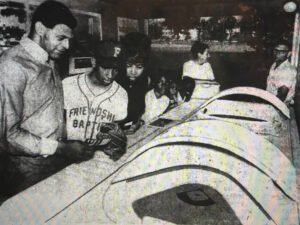

The judges appeared at rallies scheduled before the June vote, along with Whizzo the Clown and a vocal group entertaining spectators with a song composed for the occasion.

To generate support for the 1967 sports complex bond proposition, the county and sports authority organized six “Bondwagon” rallies, where voters could examine a scale model of the proposed complex. During a June rally in Kansas City’s Parade Park neighborhood, Kansas City Chiefs halfback Gene Thomas showed off the model to area residents; photo courtesy of The Kansas City Star

“For just 90 cents a month, that’s about what it will be,” they sang. “There’s a better, brighter future waiting for you and me.”

Today the 1960s vision of a downtown domed stadium is one of 10 seriously-considered-but-ultimately-scuttled projects unearthed in “The Kansas City That Never Was,” an exhibit on display through August in the Special Collections Gallery of the Miller Nichols Library at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

“Ultimately, a downtown stadium was considered just too cost-prohibitive,” said Stuart Hinds, special collections and archives curator.

“There was the parking issue, and the traffic,” Hinds said.

“Another factor was the number of downtown businesses that were going to have to relocate, and many of those companies indicated they would move across the state line to Kansas.

“Neither the city or the county wanted that.”

There were other issues. Some residents of eastern and southern Jackson County might wonder why they would consider voting for any bond package that would build a new stadium so far from their homes.

“The process was viewed as exclusionary,” Hinds said.

“So, they started looking around at other sites, and Leeds was where it landed.”

The design of what became the Truman Sports Complex, announced in May 1967, included a rolling roof. The following month Jackson County voters approved bonds to finance construction of the complex. In 1971 county officials, citing cost concerns, said the roof likely would not be built; Rendering courtesy of the Dutton Brookfield Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri

The benefits of the Leeds location, Hinds added, included lower land acquisition costs and easier access.

By then Interstate 70 and Interstate 435 were in place.

Still another concern was the use of condemnation, and the fear of litigation that would stall progress on a downtown stadium, said Lonnie Shalton, a Kansas City lawyer who blogs on baseball and other topics.

While the use of eminent domain – which allows governments to take private property and convert it to “public use” – is familiar today in sports stadium development, it was less so in 1967, said Shalton.

Further, there would be many downtown property owners affected by a stadium project, any of whom could decide to challenge it in court.

In contrast, the Leeds sports complex location, proposed with other public works projects to benefit at least some residents of the seven outlying county townships, would figure to find admirers.

One campaign brochure highlighted a specific project – the widening of 3.8 miles of the often-congested Noland Road in Independence.

But sometimes such projects could be a tough sell with county voters, even when designed to address transportation issues both urgent and obvious.

During the 1960s Lee’s Summit drivers – even those of emergency vehicles – sometimes would have to wait at a particular railroad crossing for trains to pass.

“With only one fire station in those days, precious time could be lost should your house be located on the wrong side of the tracks,” said Mark McKee, son of William McKee Jr., Lee’s Summit mayor from 1972 through 1978.

The elder McKee, who later would serve a term as sports authority chair, volunteered to promote support for a bond measure that would finance construction of an underpass, freeing drivers from such interminable freight train interludes.

Still, some residents resisted, McKee said.

“Many citizens, particularly from more rural areas, could still remember the hardships of World War II and the bitterness of going broke during the Depression,” McKee said. “Taking on any kind of debt, public or private, for nearly any reason, was bad business to be avoided.

“Voters passed the project, although not unanimously.”

Bipartisan Harry

One reason voters approved the 1967 stadium bond issue, according to Shalton, was that the county sports authority – set up by the Missouri legislature in 1965 – was officially bipartisan.

Harry Truman had used a similar game plan some 40 years before.

“Before 1967, you have to go back to Truman to find a major county bond issue election,” said Shalton, who served as Jackson County Democratic Party chair from 1974 through 1978.

That was the first road bond issue advanced by Truman, elected in 1926 as Jackson County presiding judge.

Truman had campaigned on a road-building program, replacing what then were known as the county’s many miles of “pie-crust” roads that would crumble like pastry to a fork after wet weather.

Political machine boss Tom Pendergast had warned Truman against scheduling such an election, believing voters simply would expect the money to be stolen or squandered. Truman proceeded anyway, appointing a bipartisan duo of engineers – one Democratic, the other Republican – who would supervise construction and expenditures.

“He wanted to convince voters that the improvements were necessary and to personally assure them the money would be used honestly,” Shalton said.

In 1928, voters approved the $6.5 million road measure by a three-to-one margin.

The Jackson County Sports Authority, established by the Missouri legislature in 1965, was officially bipartisan. Authority commissioners hoped that would help generate voter support for the 1967 stadium general obligation bond proposition, as it had almost 40 years before when Jackson County Presiding Judge Harry Truman, campaigning for a $6.5 million road bond proposal, appointed both Democratic and Republican road engineers to supervise the project. In the early 1930s Truman (center) posed with road engineers Alex Sachs, Democrat, (left) and Nathan Veatch, Republican, (right); Photo courtesy of the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

Shortly before the 1967 vote Truman endorsed the bond package, including the stadium proposal.

If the subsequent construction of the Truman Sports Complex nudged the community’s center of gravity a little to the east, the facility also served as a recognized community assembly point, Hinds said.

“It gave the people in Kansas City and eastern Jackson County a place to come together,” he said.

In 1970, the Jackson County Court approved a resolution naming the complex for Truman.

“With Harry Truman being so identified with Independence, the name was a unifying factor for the whole county,” Hinds added.

Not-so-convenient parking

Meanwhile, neither Kansas City franchise owner trusted the other in 1967, said Bob Jacobi Jr., executive director of the Labor-Management Council of Greater Kansas City.

Among the several reasons the sports authority had preferred the dual stadium project at Leeds was the challenge of deciding which franchise would serve as a single stadium’s principal tenant, which then would sublease the stadium to the other.

“That would never have worked,” said Jacobi, son of Bob Jacobi Sr., a member of the Jackson County Legislature from 1975 through 1979. (A county legislature and chief executive had replaced the old county court judge system in the early 1970s.)

“Neither one trusted the other, and knowing Charlie Finley, that is not surprising,” Jacobi said.

“With him and Lamar Hunt, you could not find more opposite personalities.

“That was my dad’s reading of it.”

Following the Kansas City Athletics’ last-place finish in 1967, Finley moved the team to Oakland, California.

The following January the American League awarded a baseball expansion franchise to Ewing Kauffman, president of Marion Laboratories. In 1969 the Royals played their first game at Municipal Stadium.

By then many were wondering whether there would be enough money to build the sports complex with the rolling roof, a key feature of the plan voters had approved.

Kansas City Star sports columnist Joe McGuff had explained that while the cost of building the twin complex then was estimated to be just under the $43 million originally advertised, the price of a rolling roof was estimated to cost an additional $8 million.

“The complex cannot be built as originally planned for the money available,” McGuff wrote in May 1968.

This was a bad look for Kansas City, Sports Illustrated insisted later that month.

“New venues, new stadiums, new leagues are all wonderful things – but not when they leave citizens of a community feeling gulled.”

Several Kansas City area officials participated in the July 1968 sports complex groundbreaking, including Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt, second from right; photo courtesy of the Jackson County Historical Society

But there would be amenities.

In 1970 Hunt announced the football stadium would be known as Arrowhead, and that the team would construct a stadium club – with paid membership limited to 750 – as well as many private “Golden Circle” suites, intended for corporate clients.

The posh upgrades struck some as having a whiff of privilege.

“The announcement by the Kansas City Chiefs to set up exclusive club facilities on public property seems to me to be just about as gauche as we can get,” wrote Star reader W. Marshall Giesecke.

“When do they plan on having pre-game entertainment between the gladiators and the lions?”

If Arrowhead was to have “a touch of class,” wrote Robert W. Lewis, author of “The Harry S. Truman Sports Complex: A Rocky Road to the Big Leagues,” a study published in 1977, “it also became obvious that some people resented it.”

The sports authority made up some of the overall sports complex deficit by issuing $8.5 million in revenue bonds.

But even in 1971 it still was uncertain there would be room in the budget to complete access roads in a timely manner.

New Jackson County Presiding Judge George Lehr said the county was considering a temporary solution of directing fans to park at Blue Ridge Mall and a nearby drive-in theater and ride buses to games.

Arrowhead Stadium, under construction in 1971, would host its first Kansas City Chiefs game the following year; photo courtesy of the Jackson County Historical Society

‘Sense of self’

When the Chiefs played its first game to open the roof-less Arrowhead Stadium on Aug. 12, 1972, its northeast ramp was not completed, some restrooms and concessions stands were not available, and a temporary sound system proved insufficient to project the several speeches within earshot of all the reported 78,190 fans present.

Little of that seemed to matter at the time, said Michael MacCambridge, author of “The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America,” published last year.

The book details the growth of spectator sports during the decade, especially as experienced on television. Arrowhead, along with Texas Stadium, the new home of Dallas Cowboys that had opened in 1971, grew familiar to those watching from couches across the country.

“They both were the harbingers of new sports stadiums as palaces,” MacCambridge said.

That seemed especially true given the striking design of the twin Kansas City stadiums, as rendered by the local architecture firm Kivett & Myers.

“When the Chiefs played its first preseason game in 1972, I was nine years old and I remember going into Arrowhead and feeling like I had just stepped into some new science fiction world,” he said.

“It was the sports equivalent of the Jetsons.”

Today, the then-futuristic complex is not part of the Kansas City that never was, but part of the Kansas City that occurred.

It boasts a 50-year legacy, having served as site of some of Kansas City’s most authentic moments of community joy, such as Game Six of the 1985 World Series, or the “13 Seconds” Patrick Mahomes playoff game in 2022.

In 1984, when Michael Jackson and his siblings debuted their “Victory” at Arrowhead, Kansas City found itself part of the national zeitgeist.

Today the sports complex seems almost a natural topographic feature. When approaching from the east on I-70, drivers can see the complex draw nearer like a remote isolated butte, or perhaps a distant ship’s smoke on the horizon.

Pink Floyd did play Arrowhead in 1994.

So did Taylor Swift in 2023.

“I shudder to think about what Kansas City might be like today without the Truman Sports Complex,” said MacCambridge.

The Truman Sports Complex opened in 1972-73 and both teams have a lease that expires in 2031 with the Jackson County Sports Complex Authority; photo courtesy of Visit KC

“When he was mayor of Kansas City, Emanuel Cleaver used to say that without the Chiefs and Royals, Kansas City was Omaha or Des Moines.

“Obviously, that was hyperbole, but it made a point.

“There are all kinds of disagreements about the economic impact of stadiums, but I think the value of a sports team goes far beyond economic value, and goes to a city’s sense of self.”

The sports complex stadiums, he added, “are our gathering places, where people from different areas and demographic groups come together.

“Just because we can’t quantify that doesn’t mean that doesn’t have value.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016.