The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum’s redevelopment of the old Paseo YMCA is nearly complete, according to NLBM President Bob Kendrick, who said the renovated building will help the museum share the history of the Negro Leagues with generations to come.

Set to open in late spring or early summer, the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center, 1824 Paseo, near the 18th and Vine Jazz District, is expected to provide students with real-life applications of math and science concepts through the lens of baseball, and the history of the Negro Leagues.

Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, with a cutout of baseball legend Buck O’Neil; photo courtesy of Greg Echlin, KCUR 89.3

“It gives us an opportunity to find a meaningful way to get kids, particularly urban kids, more interested in math and science, but also learn Negro Leagues history at the same time,” Kendrick said. “We think this is cutting edge. I don’t know of another facility in an urban community that will offer this kind of experience.”

Kendrick said the museum — which he called “Kansas City’s gift to the world” — is working to create a curriculum that will offer educators “an additional tool” to get students more engaged.

“You’ve just got to believe that if I can make the subject matter more interesting, then academic achievement is going to grow, because students are more interested,” Kendrick said. “It becomes in some ways experiential now — you’re actually able to apply what you’re learning.”

Click here to explore the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City’s historic 18th and Vine Jazz District.

In addition to the NLBM Sports Science Center, the renovated building will house a research library complete with rare books, oral histories, and archives from African American newspapers — all with the goal of providing visitors with a central repository of Negro Leagues history.

Beyond that, the museum will use the expansion to create additional exhibits, classrooms, and offices, all of which Kendrick said are badly needed to meet greater demands.

“Right now we’re forced to run our programs down in the gallery. . . so we knew that we needed additional space to maintain and grow these unique programming opportunities,” Kendrick said. “There are still so many stories to be told, and every time that I do want to tell a new story, I literally have to tear something up. That is not optimal.”

The Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center will also feature a mixed-use event center and 13,000-square-feet of office lease space, both of which will generate revenue and operating income for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kendrick said.

Museum’s spiritual leader

The new facility bears the name of John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil Jr., who played for and managed the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League and later became the first Black coach in Major League Baseball.

“The thirst for knowledge always kept him going, which is why I called him a renaissance man,” Kendrick said. “He said he wanted to learn something every single day, and I do think that gave him an even greater zest and zeal for life — it motivated him. Education meant the world to him.”

Who was Buck O’Neil? Click here to learn more about the Kansas City baseball legend.

Growing up, O’Neil was denied the opportunity to attend an all-white high school in his native Sarasota, Florida, according to Kendrick, who said O’Neil was awarded an honorary diploma years later.

“He wanted to see kids learn about the history of the Negro Leagues, but maybe more importantly, the life lessons that stemmed from this incredible story of triumph over adversity,” Kendrick said.

O’Neil was instrumental in the establishment of the museum in 1990, and always believed the creation of this educational center was as important as any other aspect of his legacy, Kendrick said.

“When he didn’t get in the Hall of Fame in 2006, he made it very clear that the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center was indeed his Hall of Fame,” Kendrick said. “Education was always at the forefront of Buck O’Neil’s existence.”

O’Neil was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame in July 2022, which Kendrick said bolstered the museum with “more than just renewed hope and optimism.”

“It’s the realization of something that we had been working so diligently on for so many years,” Kendrick said.

Even now, more than 15 years after his death, Kendrick said he feels that O’Neil is still “guiding my footsteps.”

“Spiritually, he is still leading this museum, and has re-energized and created opportunities for us to continue to grow and advance this museum.”

100-year-old link

Just like Buck O’Neil, the story of the Negro Leagues cannot be told without the Paseo YMCA, one of the first Black YMCA locations in the country.

On February 13, 1920, Andrew “Rube” Foster led a group of eight independent Black baseball team owners into a meeting at the Paseo YMCA.

When they emerged, they had come to an agreement that would establish the Negro National League, the first successful organized Black baseball league.

“So for me, the Paseo YMCA is the most significant Negro Leagues artifact in existence,” Kendrick said. “Now, we don’t oftentimes look at the old buildings as being an artifact, but in this case we do, because it is the very place that the story that we are now charged with preserving began.”

RELATED: A 1920 meeting at the Paseo YMCA gave Black baseball a league of its own

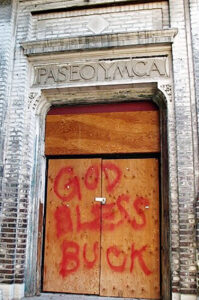

More recently, however, the building had sat abandoned for decades, Kendrick said, until philanthropist Landon Rowland purchased the structure from the city in the early 2000s and donated it to the museum with the hopes of establishing a future expansion.

The project took longer than hoped, Kendrick admitted, as the NLBM adopted a phase-by-phase approach to renovations in order to protect itself from financial risk as a nonprofit organization.

After more than a decade of gradual redevelopments made while maintaining the building’s structural integrity — a project which Kendrick said was spearheaded by Ollie Gates — the event space was finally ready to open, only for the building to be vandalized and flooded in June 2018.

“Needless to say, my heart just sank in my gut, because I understood at that moment that all this work that we had done was likely destroyed,” Kendrick recalled of seeing the damage.

To make matters worse, NLBM’s insurance company refused to pay for the damages that totaled roughly $500,000, forcing the museum to essentially restart the process.

“The story of the Negro Leagues is about triumph over adversity, and so as I tell people all the time, as a steward of the story, you can’t wallow in self pity,” Kendrick said. “You’ve got to figure out a way, because it would be doing a disservice to all of those who call the Negro Leagues home.”

Through a combination of private and public funding — including big contributions from MLB and the Royals organization — the museum did indeed find a way to make the necessary renovations twice-over.

“There has been nothing traditional about how this museum has emerged through, now, almost 33 years of its existence,” Kendrick said. “In many ways, it makes the journey that much more meaningful, that much sweeter, because you’re doing it against the odds.”

Black baseball equals legacy of success

As the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum embarks on a new chapter in its history, Kendrick knows its continued salience relies on conveying the historical importance and relevance of Black baseball to visitors young and old.

The now-repaired front door of the former Paseo YMCA, now the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center

“Historically, we’re doing what we’re supposed to do, and I think civically as well,” he said. “We’re just doing what we have, as an institution, an obligation to do. Not many museums come along into existence shouldering the weight of an entire community, and we welcome that challenge. I do think that’s why so many identify with this museum.”

The museum offers an opportunity for non-Black people to learn about stories of Black success, Kendrick said, so that they have a more complete and accurate picture of African Americans beyond slavery, police brutality, racism, and civil rights injustices.

“Most stories in the annals of African American history have been these downtrodden kinds of stories,” Kendrick said. “Now, we’ve always risen above it, but it’s been the story of slavery, our quest for civil rights in this country. Rarely are our success stories focused on.”

“That is part of my journey towards citizenship in this country,” he added. “But my success stories are equally important, because you’re not going to find a whole lot of commonality in those things that I’ve had to experience in this journey in this country.”

“Not too many folks can relate to that,” he continued. “You might empathize with it, but you can’t relate to it. But my success stories you can relate to, and you need to see those images of me. The story of the Negro Leagues is one of those great African American success stories, and to me, that’s what makes it so pertinent, so powerful, and so compelling.”