Editor’s note: The following story was originally published by Flatland, the digital magazine of Kansas City PBS and a fellow member of the KC Media Collective. Click here to read the original story or here to sign up for the weekly Flatland email newsletter.

T-Mobile in Kansas City has been as quiet as a pin drop since it merged with one-time local corporate icon Sprint in April 2020.

There have been no razzle dazzle press extravaganzas.

Just as the deal was consummated, COVID-19 hit. Workers retreated to home offices in spare bedrooms and basements across Kansas City. The company quietly went about its work of marrying two back office operations and integrating far-flung assets.

With Oracle now swooping in to snap up another homegrown corporate power, Cerner, it might be worth considering how a similar corporate marriage is playing out — reasonably well, it seems.

Checking back in with what remains one of the city’s most important employers, T-Mobile has plenty to report.

Its local employment remains robust, as promised, groundbreaking new technologies and strategies are being pursued here and local charitable giving by the company whose name sits atop downtown’s T-Mobile Center continues apace.

It would all put a smile on the face of Cleyson Brown, who at the end of the 19th century launched the phone company that would eventually become Sprint in Abilene, Kansas.

T-Mobile key executives heading up product development and human resources confirm in separate interviews that notwithstanding the skepticism of some who recall the vexed merger of Sprint and Nextel many years ago, the latest two-headquarters scheme — anchored in Bellevue, Washington, and Overland Park, Kansas — is working.

Who would have thought: communication has made it all possible.

Notably, employment in both headquarters cities remains pretty even — about 5,000 in Overland Park and a shade above 5,000 in Bellevue.

And while COVID raged, T-Mobile upgraded the former Sprint headquarters buildings here, a sign it has no plans to leave. Executives said they are eager to have excited, forward-looking workers return to the premises.

A different spirit reigns than the era Sprint veterans recall, with its waves of layoffs as Sprint chieftains’ grand strategies crumbled, one after another.

Some remember the huge French and German flags that fluttered from Sprint’s one-time headquarters on Shawnee Mission Parkway in the 1990s, when the two European companies and Sprint formed the Global One alliance. The Europeans acquired a 20 percent share of Sprint for $4.2 billion. That joint effort collapsed in 2002.

A $118 billion merger between WorldCom and Sprint spontaneously combusted in 2000.

Sprint then acquired Nextel in 2005 in a $35 billion deal, which Forbes later headlined as “One of the Worst Acquisitions Ever.” Sprint went on to post a $29.5 billion fourth quarter loss in 2007, mostly from a writedown tied to the merger.

Sprint employment in the Kansas City area peaked at about 22,000 in 2002, just about when Sprint was putting the finishing touches on its massive campus north of 119th Street and west of Nall Avenue. Employment then steadily plunged, reaching about 5,500 by 2019. Much of the campus is now occupied by other employers.

T-Mobile now has just over 1 million square feet of the 3.8 million square feet in the campus, making it the single largest tenant, according to Chad Stafford with Occidental Management, the owner and manager of the property now called Aspiria.

Stafford said that the campus was fully occupied by Sprint upon completion around 2002-2003. Sprint started subleasing space by the end of that decade, he said.

“T-Mobile has embraced the campus,” Stafford said. “We are mostly past the transition from Sprint to T-Mobile.”

T-Mobile is now holding the line on local employment while doing some path breaking strategizing on future products.

T-Mobile’s global accelerator program, with tech engineers on the prowl for emergent 5G disruptive technologies, is based at One Kansas City Place in downtown Kansas City’s tallest building.

What emerging technologies?

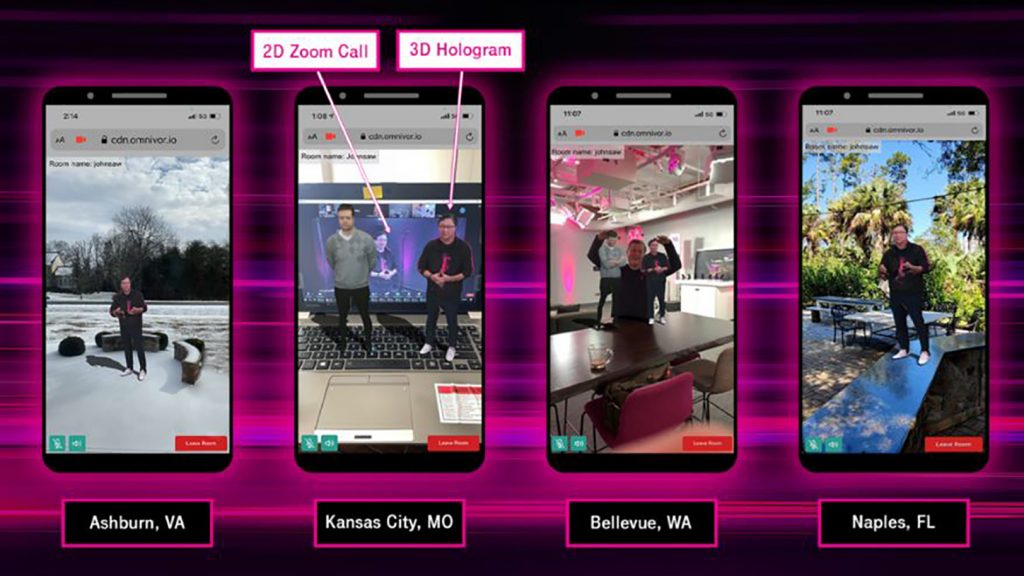

Brace yourself. The next generation of phone videoconferencing will allow a three-dimensional hologram to pop off your screen.

John Saw, T-Mobile’s executive vice president of advanced and emerging technologies, and his team conducting early testing of holographic telepresence technology during a meeting in February 2021. (Courtesy | T-Mobile)

Magic sports glasses will enable fans to see important stats when they look at Salvy at the plate or Mahomes fading out of the pocket. That technology has been demonstrated to the top brass of T-Mobile’s hometown teams, the Seattle Mariners and Kansas City Royals.

New tools will help medical students study cadavers, high school students learn algebra and e-cyclists negotiate bike trails.

Intent on acting like a headquarters operation locally, T-Mobile through its T-Mobile Foundation steered $815,000 in grants, sponsorships, employee giving and volunteer efforts to 500 nonprofits in the Kansas City area since August 2020, according to spokeswoman Brandy Sloan. She said Sprint gave $500,000 to $1 million a year in its final years.

John Saw, T-Mobile’s executive vice president of advanced and emerging technologies, who was based in Overland Park from 2014-2020 as Sprint’s chief technology officer, said the merger of Sprint and T-Mobile’s “complementary assets” has resulted in “a more formidable competitor.”

Key to that is research and development of 5G and antenna technology done at Sprint in Kansas City. “We started investing in it in 2015,” Saw said. Three years later, its rollout began.

“5G” is the fifth generation of mobile technology that is touted as the highway that will connect everyone and everything at blazing speeds.

“Kansas City will remain a major brain trust,” Saw said. Sprint’s legacy as a “scrappy underdog” lives on within T-Mobile’s evolving culture, he said.

Sprint’s most legendary accomplishment was deployment of a 23,000-mile fiber-optic network starting in 1980 that paved the way for America’s telecommunications and computing revolution.

It cost $2 billion and was deemed a “bet the company” gamble by then Sprint Chief Executive Officer Paul Henson. It turned out to be a winning bet even if the company early on had trouble sending out accurate bills on time.

Fast forward four decades. T-Mobile is now spending $60 billion building out “the best 5G network in the country,” Saw said. T-Mobile is battling rivals AT&T and Verizon.

“The race is not even fair,” Saw said. “Our 5G footprint is bigger than AT&T’s and Verizon’s combined.”

The reason? “Because we have the right spectrum assets because of the merger,” Saw said.

John Saw, T-Mobile’s executive vice president of advanced and emerging technologies, (second from left) and team in a studio surrounded by cameras capturing volumetric images to create holograms displayed on mobile devices. (Courtesy | T-Mobile)

T-Mobile also has big plans on bringing broadband to the home à la Google Fiber.

To gather intelligence on new telecom technology, T-Mobile has taken an “accelerator” program launched by Sprint and put it on steroids.

“It originated from Kansas City,” Saw said. “As a new company, we expanded it to go global. We’re taking something Sprint has built and made it bigger.”

Startups in Israel, the United Kingdom and Canada have been tapped.

“We believe innovation happens everywhere,” Saw said. “As a new company we have to build something bigger than ourselves.”

Outside the T-Mobile orbit, local business and civic leaders wondered if the demise of Sprint would translate into an exit of high-tech employment from the metro.

That has not been borne out, said Maria Meyers, executive director of the University of Missouri-Kansas City Innovation Center. A recent study showed the number of high-tech startups in the city that hired their first employees stood at 932 last year, about even with the level reached in 2019.

“At least in the startup community, we’re not seeing a drop in the tech community,” Meyers said.

Economist Frank Lenk, longtime observer of the local scene, said that the city has been on a roller coaster ride with Sprint for several decades and now, possibly, has arrived at a better place. Lenk is director of research services at the Mid-America Regional Council, where he has been a fixture for 43 years.

“During the 1990s, telecom was an industry of the future. It (Sprint) gave everyone a sense of pride,” Lenk said. “When it started declining, it was a drain on our economy. The question then was, ‘What would be next if Sprint would not power our economy anymore?’”

New stars emerged, like Cerner — acquired by Oracle in December — and Garmin, Lenk said.

“Now the development strategy is to build a deeper bench and not be as reliant on one industry,” Lenk said.

T-Mobile has every intention of keeping a seat of some prominence on that bench.

“Kansas City will remain a key employment center for the new T-Mobile,” Saw said.

T-Mobile executive offices are starting to buzz once again as many workers, inoculated against COVID, return to work. T-Mobile looks to the day when their ranks swell.

“We want to get people back to experience the culture and grow pride in the company,” said Deanne King, T-Mobile executive vice president and chief human resources officer. She formerly worked 30 years with Sprint.

Martin Rosenberg is a Kansas City writer who hosts the U.S. Department of Energy podcast, Grid Talk, and covered Sprint for The Kansas City Star in the 1990s.

This story is possible thanks to support from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a private, nonpartisan foundation that works together with communities in education and entrepreneurship to create uncommon solutions and empower people to shape their futures and be successful.

For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn