The word was simple — sprinkled into a potentially impactful email introduction last week with little fanfare — but for Lee Zuvanich, reading it felt like Christmas morning.

His.

“When I came out on LinkedIn this summer — with my pronouns and everything — it wasn’t really a choice,” said Zuvanich, a trans man who now uses he/they pronouns, detailing his hopes for acceptance in a new identity amid terror over how the transition would impact his career. “I started testosterone — which gave me some of the most positive feelings of total relief — and I knew that would change my appearance and voice, so I was going to have to get over my fear.”

A casual, late-Friday-afternoon message four months later, the email from TripleBlind founder Riddhiman Das was meant to merely connect Zuvanich, an emerging serial founder and entrepreneur, to the partners at the prominent Kansas City venture firm KCRise Fund.

The intro teased Zuvanich’s new tech startup — Appsta, a custom software sales platform that democratizes the way people purchase services — and mentioned moral support and guidance from the likes of Das and well-known Kansas City entrepreneur Toby Rush.

But then Das did Zuvanich one better.

“While I’m starstruck by these awesome people, I think it might be even better that Das USED MY CORRECT PRONOUNS,” Zuvanich said with excitement, recalling the email. “I kinda want to cry.”

The moment came after weeks of Zuvanich being misgendered by nearly every new client and potential investor he’d met, he said. And he didn’t correct them, he said, in part because he wants their business or investment, but also because he hopes they’ll either eventually accept him or keep moving.

Most do, he said.

“I was ready to lose my business when I first came out,” said Zuvanich, also founder of Adva Digital Solutions and former COO of Stenovate, one of Startland News’ Kansas City Startups to Watch in 2020.

This spring, he was named to Forbes’ Next 1000 list of “entrepreneurs putting compassion at the heart of their businesses” for his work with Adva Digital, but the female-presenting photo that accompanied his profile dogged him as he continued weighing the risk of going public.

“I was sure — 60 to 70 percent — that everything I’d worked so hard for was going to go away,” he said. “I thought I was going to have to get a job working for someone else’s company who was going to pay me a lot less. And they’d be cool or whatever, and I’d be their token who they’d say they were going to protect. I was ready for that. But instead everyone has kind of rallied around me.”

And while moments like Das’ email introduction stand out, Zuvanich was quick to admit he keenly understands others’ confusion surrounding pronouns and the nuances of gender identity, he said.

“I almost feel like trans people are always coming out with cute graphics for Instagram that say ‘Here’s how you address us in public’ and ‘Here’s what you need to know about your trans friends.’ I personally feel just as lost as CIS people when it comes to ‘How do I interact professionally with people who may or may not even agree with … whatever?’” Zuvanich said. “I know that’s not really my problem — but on a professional level, it absolutely is my problem. I just wish there was a guide. … I wish I had a way of knowing how to navigate that with sensitivity on both sides.”

Not sure the difference between “cisgender” and “transgender”? Click here for a glossary of terms from the Human Rights Campaign.

Zuvanich sat down with Startland News for a series of candid conversations over three months, discussing his journey — not only the process of coming out professionally on social media and in-person, but the years-long struggle behind the scenes to realize the truth behind his own conflicted feelings.

“People deserve a snapshot of someone going through this instead of just someone who has fully passed through all of the pain, come out on the other side, and is fully living their best life,” Zuvanich said. “It’s been this messy, painful birth of my real identity and I wasn’t prepared for it.”

Dressed for drag

Zuvanich initially came out as non-binary seven years ago, he said, changing his name to the more gender-neutral “Lee” and shattering assumptions that he was “a blonde, female-bodied, yoga instructor with what looked like a perfect little nuclear heteronormative family that went to church.”

Still, he was walking a line — not feeling like a woman or trans, and never comfortable in his own skin … or heels, he said.

For a time, Zuvanich and his partner, Charlie, were perceived as lesbians. And Zuvanich could play a more socially acceptable role he thought was needed to safeguard his family and livelihood, he said.

“I had very expensive makeup and would wear really nice clothes and heels, and try to look the part. And then when I felt like I had achieved it and I looked right, then I would feel all this euphoria. Like ‘I did it! No one knows!’” he said. “The way people probably feel when they dress up for cosplay and they look like the character.”

“But it never felt true to me … It was a numb, out-of-body experience,” Zuvanich said. “I didn’t feel in touch with my body at that time. I was in a very cerebral occupation, focused on what I could deliver professionally and on making other people happy.”

He was especially worried about how the tech community, who he perceived as generally conservative, would react to any other representation of himself — though he still didn’t yet understand his feelings of gender dysphoria.

“I was keeping it to myself mostly,” Zuvanich said. “But when someone called me ‘she,’ it felt like death by 1,000 paper cuts.”

“And it made me feel scared — like I would jeopardize a massive, multimillion-dollar project with a construction client or something,” he continued. “And I didn’t want to be taken off a project because I made someone uncomfortable. So I just kept it to myself.”

“And when people started putting pronouns in their email signatures and they were like, ‘Oh, it’s for visibility,’ I felt so much pressure to do that for the trans community. But then I felt like I couldn’t, because it didn’t feel safe to me. And my first priority was to have a stable career so that I could take care of my family.”

“So the safest thing for me to do was to just keep doing what felt like drag or cosplay and just dress up,” he said.

The pandemic was the beginning of the end for his charade, Zuvanich said.

“I didn’t have to play that role for eight to 10 hours a day anymore, and I was able to just be at home with my family that loves and supports me,” he said, noting his family was using they/them pronouns for him that helped create a distinction between life outside and what it could look like if he was actually able to be himself.

“And then I got vaccinated, and we all started going back to work and meeting with people again. There I was again … wearing dresses and feeling numb and disassociated,” he said.

Click here for resources on understanding the trans community and coming out or transitioning in the workplace.

The egg finally cracks

Whenever Zuvanich tried to unpack those feelings, they became too painful and overwhelming, he said.

“So I’d repress it again and be like, ‘No, that answer can’t be right. There’s too much internal conflict. That must mean I’m non-binary because I feel like I’m ping-ponging between these two choices — being perceived in the world as a binary, CIS woman and feeling safe with that or telling everyone I’m trans and feeling unsafe and honestly really bad about myself,” he said. “Because if I looked in the mirror, I didn’t see a man. I didn’t feel like I was valid. And I didn’t have anyone validating that for me.”

Coming out to his grandmother was also one of Zuvanich’s biggest fears, he said, recalling reasons he’d avoid exploring gender issues that he knew could bring about some challenging discoveries.

“In my mind, every time I went shopping or every time I spent money on things that were for this female impersonation lifestyle that I was living, I would look at the price of it. And I would think, ‘Do I really want to spend this? Because at some point, I’m going to come out and I’m going to have to throw it all away. I’m going to feel so stupid. I’m going to be so mad at myself,’” he said. “And then it was compulsive. I would just buy more clothes and be like, ‘Nope, can’t do it now. We’re not doing that until we have enough money in the bank and enough security in our career.’”

Not until Grandma dies. Not until the kids are grown. The list added up.

“I thought, I can’t hurt anyone in my life by doing this,” Zuvanich said. “It feels so selfish.”

However, seeing his grandmother’s and children’s welcoming reaction to his partner, Charlie, coming out as a trans man first was a watershed moment, he said. It also was brutally bittersweet, Zuvanich noted, pointing out the conflicting emotions — happiness over the acceptance of Charlie and sorrow over Zuvanich’s own unresolved gender confusion — sent him into a deep depression.

“I was in a really dark place. Like, I haven’t felt that bad since I was a teenager … maybe ever. I had an amazing time with a bunch of people who were really supportive and wonderful — but they didn’t know who I was,” he said.

He retreated into watching TikTok and YouTube videos about trans people — enthralled by the stories of people who looked like him, talking about their journeys from fear to survival.

“I had to see trans people being happy and safe and loved and more comfortable than they’d ever been. That’s what flipped that switch for me,” Zuvanich said.

“There’s this saying that when you’re trans, and you have a suspicion, but you’re not out to yourself and won’t admit it, you’re an egg. And then when you have that moment of realization, that’s when the egg finally cracks. And that’s what it feels like,” he continued. “One moment, you’re one thing. And then next — even when there’s seven years leading up to it — you’re suddenly something else.”

“And I knew that the life I had been living — if I tried to go back to it — would kill me. I’d never identified with that. It’s really dramatic and scary. But it went really deep — and when I allowed myself to feel it and acknowledge it, I cried and cried and cried.”

“I was waking up every morning and asking myself ‘Am I still trans?’ It was a negative feeling. Like waking up and remembering that you just got a diagnosis of some disease. I’m ashamed to admit it now because there’s nothing wrong with being trans, but I had years of fear built up that I had to work through.”

Need to reach a counselor or to explore crisis services? Click here to get help through the Trevor Project.

Zuvanich felt physically ill when he saw all those clothes, makeup and shoes that embodied his former self, he said. He boxed them up and tucked them away in the basement.

He got a more masculine haircut and bought new menswear.

He came out to his family. Then friends. And eventually LinkedIn.

“The way I used to feel has become inverted,” Zuvanich said. “Where before I could only feel what other people thought about me from the outside — and internally I was very numb — now I feel very alive and in touch with myself. I feel happy, peaceful, self-aware and valid. And I’m more numb to the outside world.”

Lee Zuvanich family

‘I might be trans, but I don’t want to be a man’

Zuvanich has long championed advocacy for the LGBT community, he said, describing himself as an entrepreneur who works to help women, minorities and other underrepresented people get into tech.

The idea of embracing life as a trans man long felt like a betrayal to those efforts, he admitted, noting he and Charlie both had many of the same ingrained concerns about accepting their trans identities and coming out.

“You push it all down,” he said. “Because you’re hearing all these affirming things about what it’s like to feel like you’re a lesbian, and then you feel like you don’t wanna betray the female community by going into a world of not just masculinity, but toxic masculinity.”

“You’re going to be perceived as someone who’s a threat to your current community. And all those feelings were helping keep the lid on everything for both of us.”

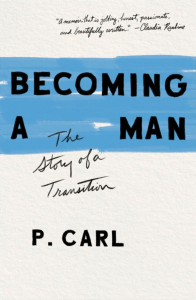

Actor Elliot Page’s high-profile coming out story, along with Zuvanich and Charlie’s subsequent reading of author P. Carl’s “Becoming A Man: The Story of Transition,” helped change the narrative.

“This isn’t really a choice. You should honor that and live your truth,” he said of lessons from the book, acknowledging that such a revelation is difficult for anyone and likely to shatter realities a person has come to trust, as well as end or dramatically change long standing relationships.

“I want to represent women in tech,” Zuvanich said. “But I can’t … because I’m not a woman.”

“And I don’t want to diminish any of the amazing women in tech by anyone using my story to say ‘He only became successful because he chose to become a man,’ which is such a weirdly bigoted way to think,” he continued.

“When I got to the moment where my perception changed and I came out to myself, it wasn’t a choice anymore. For a long time, it felt like I was just avoiding a bad decision — because the wrong choice would mean aligning myself with people who have a lot of privilege against the people who I feel like I’ve fought really hard alongside.”

“I know I might be trans, but I don’t want to be a man,” he added. “And that’s probably because I’ve had a lot of negative experiences that made me feel like the world wasn’t safe because of men.”

“At the same time, if I see a woman walking down a dark street and I can tell she instantly and instinctively feels uncomfortable because she sees me as a man and a threat — I can imagine how it hurts to be perceived in that way.”

Digging deeper into those contradictions is all part of the journey toward authenticity, Zuvanich said.

“It’s exhausting to pretend you’re something you’re not. Now I’m focused on being genuine and connecting with people on another level,” he explained, detailing his belief that trans visibility is a lifeline for people who have fewer resources.

His response now: to become more visibly queer.

“If other visibly trans people who are also professionals living healthy, happy lives didn’t exist or hadn’t gone before me to show me the way, I wouldn’t have been able to come out,” Zuvanich said. “I can now say very confidently that I am a partner to a trans man, I have two kids, and I identify myself as a trans masculine entrepreneur.”

This story is possible thanks to support from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a private, nonpartisan foundation that works together with communities in education and entrepreneurship to create uncommon solutions and empower people to shape their futures and be successful.

For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn