Kansas City is tackling its pothole problem using technology that aims to predict where they’ll emerge next, city officials said. The proactive approach also is targeting Kansas City’s crime rate.

Government officials from Kansas City, Missouri, shared details about their experience with smart, predictive technologies during a panel discussion Tuesday afternoon at the Smart Cities Conference. The event brought together government representatives from across the world to exchange ideas adaptable across municipalities.

Through KCMO’s partnership with Xaqt, a Chicago-based provider of smart city technologies and predictive intelligence, the city is testing prototype tech related to potholes on a few block-long sections of roadway, said Sherri Mcintyre, director of public works and assistant city manager for Kansas City. The goal is to deploy maintenance to those spots before the potholes even form, she said.

“I think, in the interim, it is going to be another additional great data piece for us to use for analytics to decide where do we deploy our resources for pavement rehabilitation,” Mcintyre said.

Chris Crosby, founder and chief executive officer of Xaqt, moderated the panel discussion Tuesday afternoon, which shed light on the data-driven projects at work in both Kansas City and San Diego.

The data-based culture and award-winning office of performance management in Kansas City helped Xaqt cultivate a unique relationship with KCMO, Crosby said, which included the firm hiring a Harvard statistician and physicist to figure out how to predict where potholes would form.

The city public works department then shared data with the Xaqt team on current road conditions and troubled spots, Mcintyre said.

After factoring in the weather’s impact on road conditions, especially from ice and thaw events, Xaqt developed a prototype, now being tested in three areas, including a section of Ward Parkway and a portion of North Brighton Avenue, north of Parvin Road, Mcintyre said.

‘Sexy on the surface’

Ultimately, smart city efforts should add value to projects already undertaken by the city, Mcintyre said.

“It gets down into ‘How can we take this data and use it for implementation from our different perspectives?’” she said.

Cities should evaluate whether incorporating and utilizing data from smart city projects, such as accidents or police incident reports, actually improves the infrastructure and impacts crime rates, Mcintyre said. Such smart infrastructure efforts should make a positive impact on city life, crime rates and public infrastructure, she added.

“I think that’s part of the team of approaches,” Mcintyre said. “Even though we have our own niche, it’s working together to bubble up what’s valuable.”

Developing public infrastructure to become a smart city is challenging for both government and the private sector, Crosby said.

“Smart cities are sexy on the surface, but they’re really hard work underneath the surface,” Crosby said, alluding to Xaqt’s work with the government of Kansas City, Missouri. “And through that comes a lot of trial and error. I mean, we’ve launched three different models now to get this right. And there’s a lot of scars underneath that.”

There is top-level excitement for smart cities, but much of the decision-making and budget control is managed at a layer or two below that, said Bob Bennett, chief innovation officer for Kansas City. In fact, he was “blown away” by the complexity of project implementation within city government, he said, citing Kansas City’s deployment of sensors — a prerequisite for the city’s pothole project.

“I did not appreciate the fact that the city has an immense amount of data here and a culture to use it, which none of this would have happened if that culture had not pre-existed my arrival,” Bennett said.

Mayor Sly James

‘That number makes me angry — It should make all of us angry’

Predictive analytics could also help Kansas City in developing actionable data platforms that identify and deploy resources to crime-ridden areas, Bennett said.

“When we’re sitting in City Manager Troy Schulte’s office and saying, ‘We anticipate that crime is going to occur during these hours in these general vicinities,’ that gives us then the ability to talk to community improvement districts to change the way they deploy their ambassadors,” Bennett said. “And we’re hoping to show that through that modeling, we’re able to actually have an impact on crime.”

Such a data-driven plan might not actually prevent crime, Bennett admitted, but it could help reduce the lethality of, for example, shootings by improving medical care and sending emergency responders to victims in time to save lives, thus reducing the murder rate.

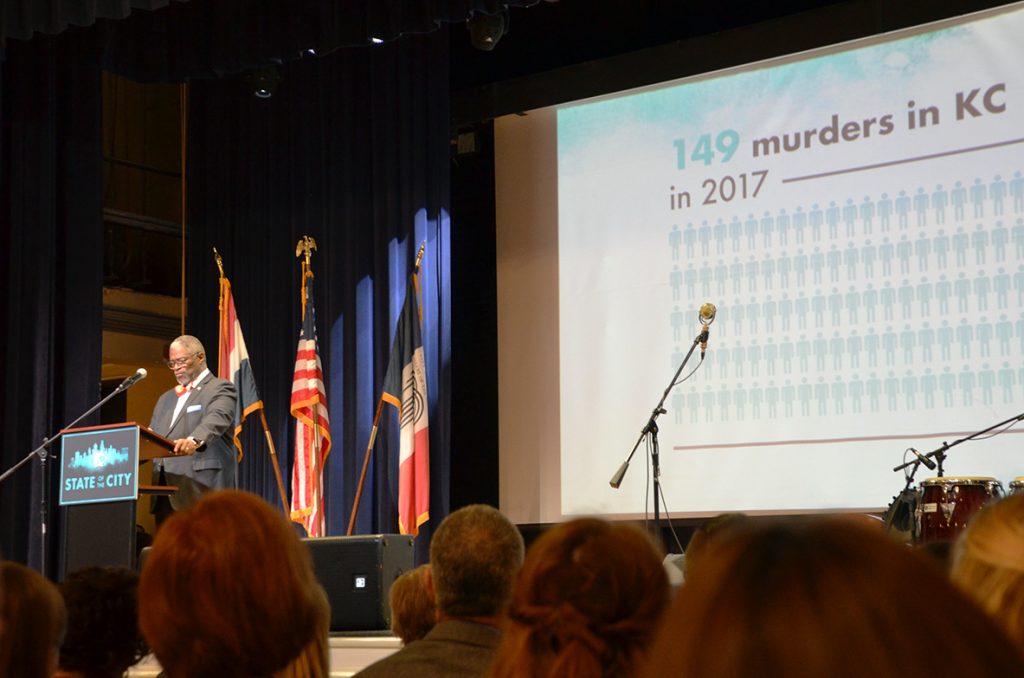

Mayor Sly James carries the burdens of those deaths every day, he said Tuesday in his State of the City address.

“In 2017, 149 people were murdered in Kansas City. That number makes me angry. It should make all of us angry,” he said. “When I go to a murder scene, I feel the corrosive force of violence in our community — it’s palpable. It tears families apart, and fosters deep, pervasive distrust between communities and police.”

“All of us deserve to live in a safe environment — no matter who you are, what neighborhood you live in, or if you’re here to visit our city,” he added. “2018 must be the year we get Kansas City off the ’10 Most Dangerous Cities’ list, and it’ll take all of us to make it happen.”

Data-based predictive tactics are a piece of that effort, he said.

‘We can predict anything given enough time and data’

Keeping government staff involved in smart city efforts presents another challenge because such efforts pull staff members away from their regular civic duties, said Eric Roche, chief data officer for Kansas City. Ultimately, it involves establishing a framework to operationalize smart -city planning and development, he added.

“(We’re) trying to come up with a standard framework of how do you do this and keep everyone involved and excited on a shorter timeline,” Roche said, adding that he thinks experiments like the city’s work with Xaqt on pothole prediction is important.

What cities do with smart infrastructure is vital as well, Crosby added.

“That’s been one of the key learnings from our perspective, is to ask the question really, ‘What does this look like when it’s implemented, and then how do we work towards that in a way that Eric [Roche] said is iterative?’” Crosby said. “Because we can predict anything given enough time and data, but the question then is, ‘OK, great, what’s the city going to do with it, and how does that actually move the needle for citizens?’”

Tech firms seeking opportunities to work with cities on developing smart projects should expect to eat some of the initial costs, said Maksim Pecherskiy, chief data officer of San Diego, which smart city leaders have recognized for its push into digital infrastructure.

“Let’s say you would build that base of prototypes and then, when you’re coming into a new client or a new city, you would say, ‘Here are some things that we can do for you; does this even sound good?’ and build on from there,” Pecherskiy said.

Cybersecurity and data privacy for both citizens and the municipality can conflict with the city government’s effort to be transparent, Roche added.