Startup community stakeholders think opportunity zones in some of Kansas City’s poorest areas could work, but only with collaboration between the government and private sector.

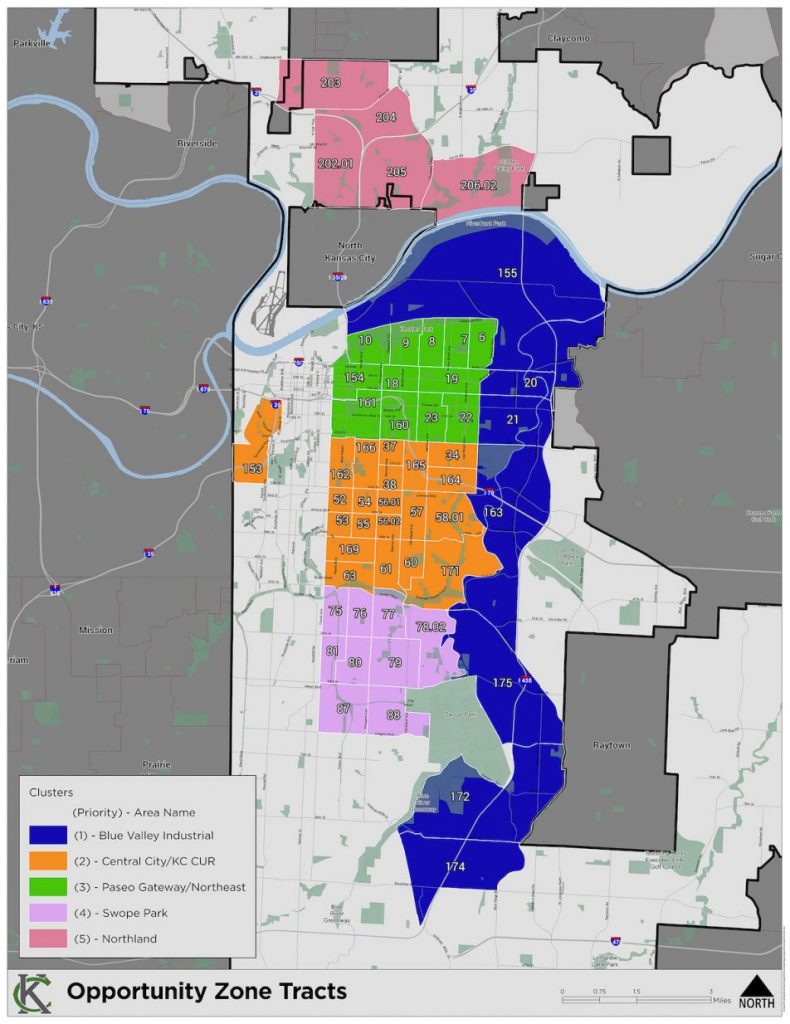

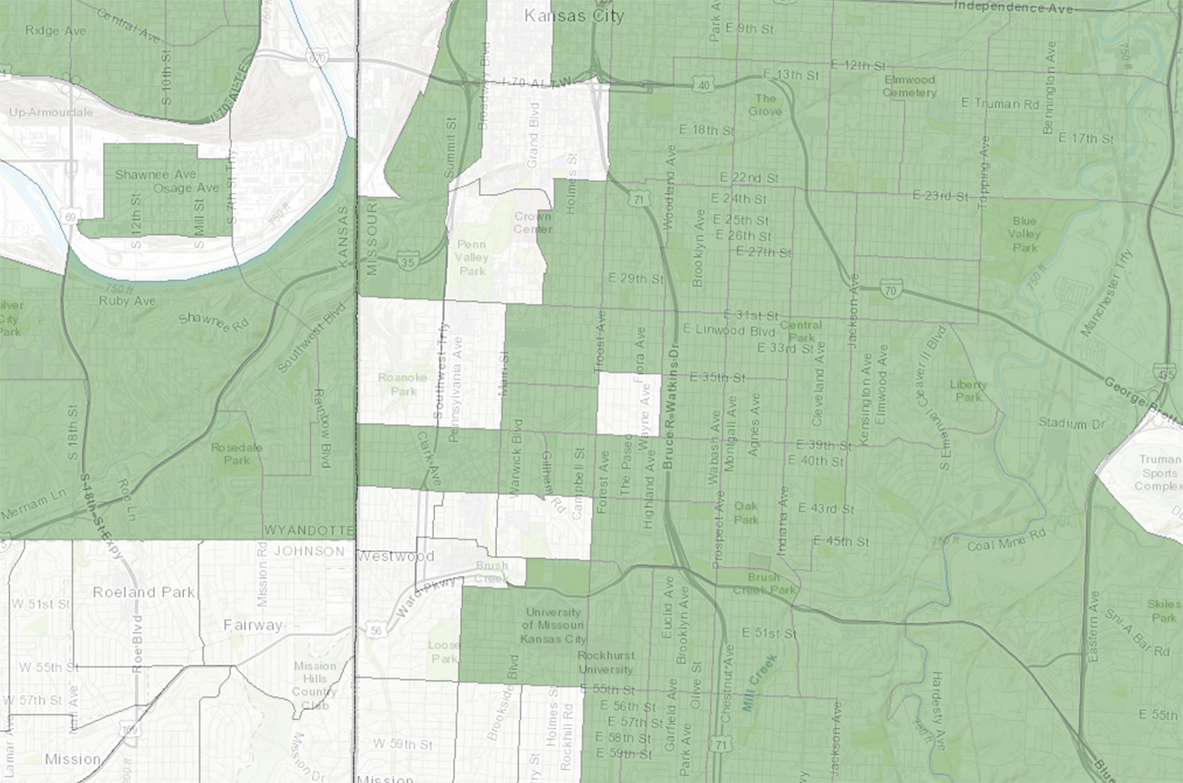

A number of low-income communities in Kansas City are eligible for designation as opportunity zones — areas in which investors may defer paying capital gains taxes over a certain period of time on business activities. (Click here to see a map of Kansas City, Missouri’s proposed zones.)

The Midtown area, for example, could see a higher density of startups on street corners if included in the opportunity zone, said Eze Redwood, co-founder and chief executive officer of Twenty30 CEO.

“Anything that makes it easier or more beneficial for a culture shift or change within the investor community in Kansas City is going to be helpful,” Redwood said.

Kansas City’s startup community is “pushing a bit uphill” because investors aren’t necessarily as comfortable with investing in areas of lower growth, he added.

“We are at the point where we have to, from a local government perspective, try some things that are different and new to facilitate the development of our entrepreneurship community,” Redwood said.

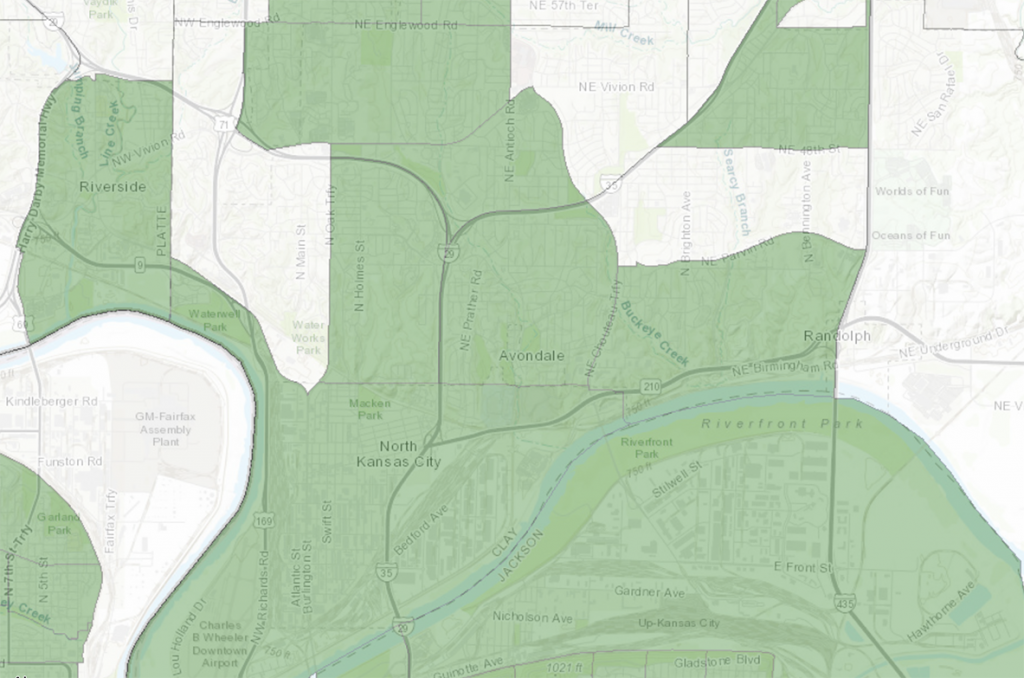

North Kansas City and Blue Valley Industrial cluster

A thoughtful path forward

Kansas City, Missouri, listed 54 census tract “clusters” in low-income communities for opportunity zone designation in a proposal submitted March 2 to Gov. Eric Greitens’ office. The clusters, in priority order, were the Blue Valley Industrial Area, Central City, the Paseo Gateway, Swope Park and the Northland.

A key focus is the Blue Valley Industrial Area, and within it the industrial space immediately south of the Missouri River, according to the proposal.

“It’s just waiting for more reinvestment in terms of industrial factories, companies that can take on lots of jobs,” said Laura Swinford, director of communications for Mayor Sly James’ office. “It used to be more heavily industrial in terms of folks actually being there and having more existing and functioning structures. A lot of that is vacant and waiting to be redeveloped.”

Stakeholders must be purposeful about revitalizing economically distressed communities, said Butch Rigby, developer of such projects as Plexpod Westport Commons and Screenland Armour Theatre.

“How do you utilize governmental programs, economic incentives, tax abatements, things like this, on the east side of our town? And how can they be effective as a tool for sparking investment and economic revitalization?” Rigby asked. “What I’ve seen is there’s been a real challenge getting people to utilize those tools in areas where economic incentives are needed most, but I also believe that there’s a reason for that.”

For example, Rigby said, no one was developing the downtown district 20 years ago; and no one was developing in the neighborhoods between Troost Avenue and Oak Street along 63rd five years ago.

“I think it’s a matter of [taking] a careful, thoughtful path toward the areas that you want to revitalize, and you cannot make them islands,” Rigby added, citing the jazz district as one example of isolation.

It’s a great idea to point economic development dollars to lower income tax areas, he said.

“But you can’t just do it willy-nilly; it’s got to be with an overall plan,” Rigby said.

Will it work?

Opportunity zones are indeed an example of the country’s overall strategy to bring capital into distressed communities, said Ruben Alonso III, president of KC-based nonprofit AltCap. But how such programs directly benefit small businesses or real estate projects is unknown, he added.

“The big question is: Is this program going to be attractive to investors?” he said. “The whole basis of the program is providing this tax deferral on capital gains, and I think it remains to be seen how attractive that’s going to be here to folks with capital gains.”

And the tax deferrals are not limited to real estate transactions; investors can have taxes deferred on any capital gains, such as selling stock, a point of interest to Alonso.

“I think it opens the door to more potential investors,” he said.

Redwood said he “definitely” thinks the opportunity zones could have an impact for the startup community.

“It will create enough benefit for investors to feel more comfortable with the potential risk that they could be taking on,” he said.

Once designated, opportunity zones will only be effective if entrepreneurs and investors take action, Alonso said.

“Is it going to be something that people want to participate in? Is it going to be a burden or just too bureaucratic to attract investors and to translate those investments into businesses or real estate projects?” Alonso asked. “But it definitely creates another source of capital, potentially, for investments.

“AltCap is very experienced in supporting other programs or other capital sources that we have, and those are always needed in economically distressed communities. There’s just not enough capital to support business investments or a real estate projects in the areas that we try to deploy capital.”

State governors have until March 21 to nominate opportunity zones. Designed to drive capital into low-income communities, opportunity zones are part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which became law Dec. 22, 2017. Opportunity zones must be economically disadvantaged to be eligible, according to the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund.

But, although opportunity zones are written into law, “there’s probably less understanding on the end user side of it,” Alonso said. In other words, the law lacks specifics on implementation and logistics.

“Even stakeholders who are going to be potentially positioned to help administer the program just don’t have enough information,” Alonso said. “Not enough guidelines or guidance has been provided by the [U.S. Department of the] Treasury around how this program will be implemented.

“Right now, I think most folks are just still kind of waiting to see what this is really going to look like in practice.”