The innovation cooking within ClusterTruck’s technology makes the rapidly expanding Indianapolis company a fresh take on the restaurant-quality food delivery scene, Christian Moscoso said.

“We are a software company with our own ghost kitchens, if you will,” said Moscoso, general manager for ClusterTruck’s new River Market kitchen, which opened in mid-December without a public entrance or dining area.

It’s by design. The web- and app-based service joins such meal delivery competitors as Postmates, GrubHub and UberEATS in the Kansas City market. But ClusterTruck’s novelty is in the company’s cloud concept and machine learning technology that allows it to take advantage of the weaknesses of early arrivers to the industry, said Chris Baggott, co-founder and CEO.

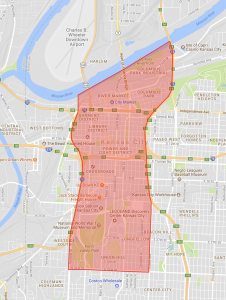

From a central kitchen, ClusterTruck accepts online orders, preps and cooks food, and dispatches drivers to hungry consumers — all within a matter of minutes, he said. Moreover, thanks to a limited delivery zone (largely downtown and the Crossroads, in Kansas City’s case) orders arrive hot to the customer typically five to eight minutes after leaving the kitchen.

Unlike its competitors, which are a third party between the kitchen and diner, ClusterTruck controls every step of the chain, Baggott said.

“Like a lot of startups, it’s good sometimes to not be the pioneer,” he said. “I love GrubHub. I’m a shareholder. They’ve created this massive system and this massive demand for delivered food, but if you read their reviews, they’re making a lot of people unhappy.”

Food quality, customer service and driver-related complaints are among the top issues for customers of such services, he added.

“But the consumer is so desperate to have prepared food delivered to them that they’re willing to suffer through all of this,” Baggott said. “All we do is come in and say, ‘Well, let’s just check off all the areas where they’re weak.’ And we have the ability to do that with hindsight.”

Chris Baggott, co-founder and CEO, ClusterTruck

Re-imagining from the ground-up

After Baggott’s previous startups ExactTarget and Compendium Software were acquired in 2013 by Salesforce and Oracle, respectively, the entrepreneur found himself facing a new challenge.

Too much hamburger.

“Along the way, I had gotten involved in the food movement, read ‘The Omnivore’s Dilemma’ and wound up buying a farm and raising pasture-raised animals and selling them direct to the consumer,” Baggott said “I was always leftover with a lot of product that I couldn’t sell at the volume that I needed.”

Slaughtering a cow for steak, for example, creates an imbalance, he said.

“Every cow gives me 400 pounds of hamburger, so we were processing lots of cattle in order to keep up with our steak demand and suddenly we had this massive $5,000 bill for freezer space just to store my hamburger,” Baggott said. “So we opened a hamburger stand to help us move that at a retail level.”

His restaurant — The Mug — gave him first-hand experience working with third-party food delivery services, he said. While Baggott recognized their usefulness, he didn’t understand why food providers would essentially transfer the customer experience to another company, he said.

“As soon as a restaurant like The Mug uses GrubHub, the customer now belongs to GrubHub,” Baggott said. “And we’re seeing that now come across in a really negative way.”

Timing is always an issue, he said.

“If you use a third-party delivery service, the restaurant is going to cook the food, but they have no idea where the delivery person is or when they’re going to show up. So the food is cooked, but it just sits there,” Baggott said. “What if I knew where the delivery person was, and I didn’t cook the food until the delivery person was the right distance away from the kitchen?”

Overcoming that obstacle with its own internal system — based on the narrow delivery zone and software that times food within an order to finish at the same time, then immediately be picked up by a driver — was ClusterTruck’s first big trick, he said.

Driving efficiency

Baggott doesn’t spend a nickel on recruiting new drivers, he said. Because they rarely leave.

“A big key is that we take our responsibility to our delivery folks very seriously,” he said. “We consider our delivery people our core constituency, even more than the customer. We built a perfect system for them. The whole key is the number of jobs per hour that they can get.”

Because they’re going between one central location and deliveries where customers meet them at the curb, drivers are able to fit four to six jobs into an hour, Baggott said

“In our system, they’re basically just running laps,” he said.

Drivers earn a flat $2 per trip, plus tips. If that trip total doesn’t equal at least $4.50, the amount is subsidized by ClusterTruck, Baggot said. The key is ensuring drivers can work efficiently and consistently, he added.

“In Indianapolis, which is our most mature market, our No. 1 delivery person went over $100,000 last year, and we had many in the $70,000 range,” Baggott said. “But we only have about 68 drivers in total, doing almost 400,000 deliveries a year — because we’re able to maximize the number of deliveries each person can make. Our goal was to create the greatest gig job on earth, and we believe we’ve done that. And it’s all algorithms and software.”

ClusterTruck chose to expand to Kansas City because of its ability to fit into the established model, he said.

“Kansas City is very much a food town. It’s very easy to get around. It’s relatively inexpensive. It’s just a great demographic,” Baggott said. “A lot of cities are like Kansas City, Indianapolis, Minneapolis and Dallas that folks consider Tier 2 cities, but the fact is they’re all very much the same in that they’re booming economically, people are moving downtown, apartments are going up everywhere, and corporations are relocating from the former suburban campuses.”

Christian Moscoso, ClusterTruck

A taste of growth

ClusterTruck’s founder considers it to be an Amazon for food. While the menu categories are branded with food truck-type names, the company isn’t tied to any particular concept, he said, noting flavors and styles can vary widely between markets.

“Our Mexican offerings in Indianapolis and Kansas City are not the same as what we’re offering in Denver, because Denver has a much different Mexican palette,” he said. “We just launched barbecue in Kansas City. We don’t offer barbecue anywhere else in the country, but we can spin up barbecue in Kansas City because the market supports it. We can make any type of food that fits the environment that we’re in.”

Moscoso, the Kansas City general manager, previously worked as kitchen manager for Jack Stack Barbecue. Many other members of the ClusterTruck culinary team came from senior positions at Cheesecake Factory, Baggott said.

With more than 80 menu items, the service offers an easy way for coworkers to share a meal over such disparate items as cheeseburgers and Pad Thai, he said. It’s another ClusterTruck trick.

“When you have a food truck out on the street, that truck is only going to make a certain amount of money,” he said. “But if you have five food trucks out there together, that’s an event called a ClusterTruck. And at those events, the individuals basically double their income — everyone makes more money because consumers want choice.”

Kansas City is ClusterTruck’s best performing new market, having opened alongside kitchens in Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio, as well as Denver, Baggott said. The company just broke ground in Minneapolis and is planning at least five locations in Texas and two in Atlanta.

“We’d like to get about 20 open in the next year and a half,” he said. “Right now, the opportunity is in the Midwest and the south.”