Plexpod Westport Commons wouldn’t exist without the historic tax credits used to make the massive renovation and preservation project financially feasible, said developer Butch Rigby.

A GOP-led tax reform bill introduced this month to simplify the tax code, however, would eliminate the Reagan-era tax credit program, which provides a 20 percent federal tax credit for historic building rehab projects that can produce revenue-generating properties like Westport Commons. [Update: The U.S. House passed the tax reform bill Thursday on a 227-205 vote. The U.S. Senate has not yet voted on its version of the legislation.]

Because of it’s wide hallways and large, challenging spaces, among other design intricacies, converting the former Westport Junior High School into a multi-use coworking space was a pricey endeavor, Rigby said.

“The costs of renovating a structure like that versus just putting a new building up are amazing,” said Rigby, who was part of the five-person development team behind the project. “Without these tax credits, we would never have taken on the junior high school project — no one could — and it would be vacant to this day.”

But the threat isn’t just from preventing the preservation of buildings like Westport Commons, the basecamp for this week’s Global Entrepreneurship Week events, said Rigby and other Kansas City preservationists and development officials.

Such tax credits have made possible dozens of recent historic rehab projects across the metro, in a wide variety of spaces.

Commerce Tower. Mac Properties apartments along Armour Boulevard. The downtown public library. The Livestock Exchange Building in the West Bottoms. The Freight House, which houses Fiorella’s Jack Stack Barbecue, Grunauer and Lidia’s. Warehouse lofts across the city. Even the former Kemper Arena, which is being transformed into a youth and amateur sports complex.

“The list is so long,” said Elizabeth Rosin, principal and owner at Rosin Preservation. “You can pretty much look at any rehab development project in Kansas City’s urban core and 90 percent of them will have used historic tax credits.”

While already-completed projects would not be affected by the elimination of the historic tax credit program, the move would have a chilling effect on future developments involving structures in need of saving, she said.

“It could be catastrophic,” Rosin said. “For projects that are in the planning and pre-development stages right now, it could just put the brakes on completely.”

And the concern goes beyond mere economics, said Bob Long, development services specialist for the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City.

“We’re talking about looking at a lot of dead historic commercial buildings — they’re all over this country,” he said. “The things that make neighborhoods vibrant and appealing, in large part, are based in the historic buildings in those neighborhoods. And it’s the tax credits that are driving those rehabs.”

How does it work?

The historic tax credit program’s impact on Kansas City has been immense, Long said.

“The equity that is generated by the sale of the tax credits reduces the amount of debt that is needed by the project. And if developers didn’t have access to that equity, they’d have to borrow more, and a lot of these projects wouldn’t have worked financially,” he said.

That assistance allows projects like Rigby’s work on the Luzier Cosmetics building on Gillham Plaza to commit resources to preserving historic design elements.

“It’s a beautiful building. It sat vacant for 20 years,” Rigby said. “There was $100,000 in fixing the brick — just to get the skin back instead of putting up a standard wall. And then there’s going to be a big mansard roof going around it that returns zero rent. But what it does is return to service is an incredible building — a building that generates property taxes, sales taxes, personal property income taxes. It’s an example of the kind of tax credit that is predicated upon performance. It’s also predicated on investing a tremendous amount of money into a historic building.”

Widely accepted statistical analyses indicate the tax credit program generates $1.20 for every $1 invested, but that’s not a complete picture of how it benefits the community surrounding a project, Rosin said.

“It’s using public dollars to invest in a public benefit: historic preservation of our shared heritage,” she said. “We get there through a variety of means. We’re creating jobs. We’re creating affordable housing. We’re creating spaces for small businesses. All through the vehicle of historic tax credits.”

Qualifying for the program takes more than an old building, Rigby said.

“It has to have significant details related to the history, whether it be a use factor or an architectural style,” he said.

The Luzier Cosmetics building, for example, was designed by renowned Kansas City architect Nelle Peters, Rigby said, noting it was her only commercial industrial building.

At Rosin Preservation, Elizabeth Rosin helps property owners get qualified buildings on the National Register so they can take advantage of the historic tax credits. Her team also works with owners, their designers and contractors to make sure they’re meeting all the requirements of the program, she said.

One such project is the Wonder lofts development at 30th Street and Troost, in which a former Campbell-Continental Baking Company-turned-Wonder Bread bakery is being transformed into mixed-use commercial and apartment space.

Historic tax credits are allowing the project to reduce its costs, which is expected to result in rents at about $1 less per square foot than would be possible without the tax credits, the project’s developers have said.

Wonder serves as an example of the tax credits’ power as a tool for action, said Jeffrey Williams, planning director for Kansas City, Missouri.

“Being able to access the historic resources on the Troost corridor to get Wonder reactivated is a really great thing,” he said.

But it also comes with a catch.

At projects like Wonder and Luzier Cosmetics, developers must strictly adhere to guidelines about what can and can’t change on the buildings, Rigby said. Windows, for example, were a key area of concern for both projects.

“You have to preserve the historical integrity of the building,” he said. “That sometimes doesn’t give you the highest and best use, but it still gives you a great use.”

Politics versus preservation

While the U.S. House version of the tax bill would eliminate the historic tax credits program entirely, the Senate’s bill would cut it in half, from 20 percent to 10 percent — still an illogical and devastating reduction, Rosin said.

“I think a lot of the people who are writing this legislation don’t understand how development works, and how big projects get financed,” she said. “Perhaps they’re assuming that if they cut the (overall) tax rates, and that puts more money in developers pockets, then that’s the same thing as providing the tax credits. But really the two operate in very different ways and have very different effects.”

U.S. Congressman Emanuel Cleaver, II, D-Missouri, told Startland News Monday he is opposed to the tax bill and the elimination of the historic tax credit program.

“I have been a long-time supporter of historic preservation programs. I understand the economic and cultural value that this tax credit provides local communities,” Cleaver said.

President Trump

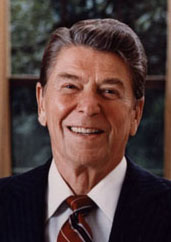

President Reagan

Implemented by President Reagan’s administration in the early 1980s, historic tax credits have a decades-long proven track record of success, Rosin said.

“It’s a program that returns more money to the Treasury than it takes out,” she said. “I don’t understand why you would cut a program like that — other than for the appearance of cutting something that benefits developers.”

President Trump notably, as a private citizen before taking office, used historic tax credits, reportedly worth as much as $32 million, to help renovate the Old Post Office Pavilion into a luxury hotel, Trump International Hotel Washington, D.C.

EDCKC’s Long said some critics might see the tax credits through the prism of handouts.

“I think there’s a big perception that this is part of corporate welfare,” Long said. “Part of this also is a rural-urban conflict. A lot of the legislators are based in rural districts and they only perceive historic tax credit projects as happening in the big cities. But they don’t realize how many projects are actually being done in their own districts.”

Rigby’s Screenland Armour Theatre in North Kansas City is an example of one of those under-the-radar projects in a smaller community — a city of fewer than 5,000 residents, the developer said.

“With the use of the historic tax credit, we were able to restore that building, put in a new sprinkler system, a new roof, new electric, a new elevator, and keep it with historic windows. We were able to turn it into commercial use,” he said. “In taxes, it returned much more than I ever received in tax credits, and did it in short order. But most importantly, you had a small town benefitting from the use of historic tax credits.”

It’s vital for communities large and small to preserve their history, Rigby said.

“No one goes to Paris to look at the new buildings,” he said.