It’s about bringing residents back to Troost Avenue, Cathryn Simmons said. And that means challenging the status quo.

“This used to be a free-for-all. Troost was the Wild Wild West of Kansas City,” she said. “You could come over here and do anything you wanted. Legally.”

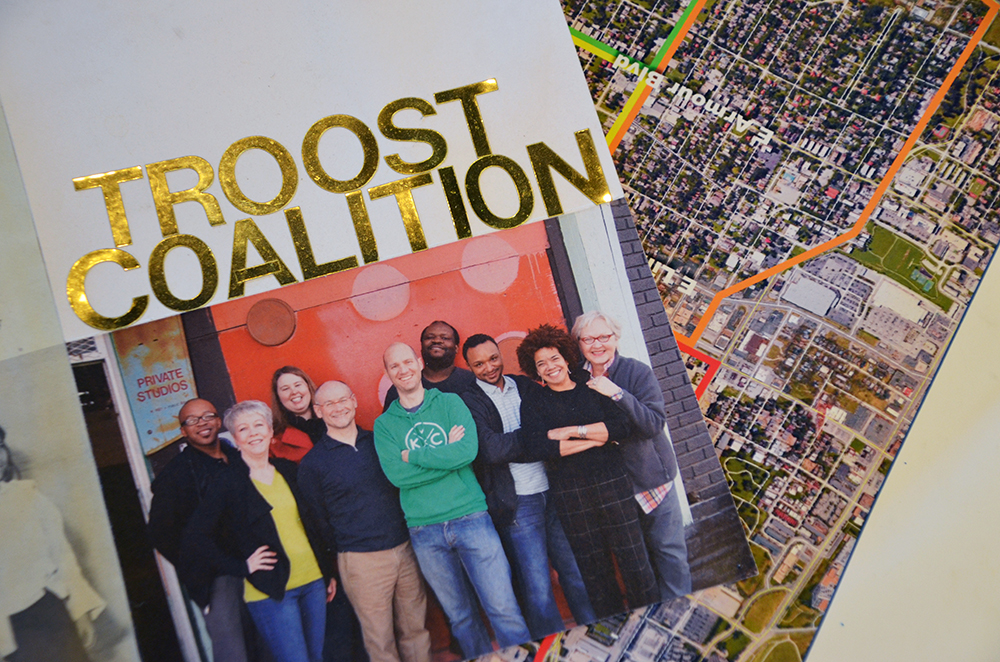

A founding member of the Troost Coalition, Simmons helped spearhead a community effort to transform not just the aesthetics of the corridor — which many see as Kansas City’s unofficial racial dividing line — but also the guidelines for development that will shape Troost for generations to come.

[pullquote]Check out the rest of Startland’s six-part series on new development on Troost Avenue, a historic racial and economic barrier in Kansas City.

Part I: Transforming Troost

Part III: Wonder lofts

Part IV: Back to Troost

Part V: Food startup Village

Part VI: Troost Collective

“We are talking about one of the major arteries of Kansas City coming back. The Troost Coalition has made a very big push to communicate that we want this to be residential first,” she said. “Our No. 1 priority is to bring people back to Troost — living here — which will strengthen the neighborhoods on both sides.”

With the backing of City Hall, the group first developed a zoning overlay that applies special land use regulations and standards for the corridor from 22nd Street to Volker Boulevard, said Jeffrey Williams, planning director for Kansas City. Now, the Troost Coalition is working on streetscape guidelines for the right of way, he said.

“This really is an effort involving communities on both the east and west sides of Troost,” Williams said. “Knowing the history of Troost as a dividing line for the city, I thought it was great that neighborhoods on both sides of the line were coming together to focus on the corridor.”

Simmons and other members of the group bristle at the notion neighbors want to gentrify Troost — that is, to displace existing low-income residents with upscale offerings too expensive for them to afford.

“It’s very hard to have gentrification on a street that has nothing,” said Simmons, who is among the few who live and work on Troost. “There are empty lots and dilapidated buildings — buildings falling down. Troost doesn’t have a gentrification problem. It has a bare lot problem.”

For better or worse, developers have their eyes on Troost because of the corridor’s affordability and opportunity as a profit center, Simmons said. Troost Coalition members aim to ensure such projects fit the needs and guidelines set forth by the community.

A quick drive shows the corridor already is being transformed. Kansas City Public Schools purchased and moved into several buildings at 29th and Troost for a new, centrally-located headquarters. The nonprofit youth and education organization Operation Breakthrough is expanding at 31st and Troost. Half a block north, a new health-focused business, Ruby Jean’s Kitchen and Juicery, will soon open a trendy new location at 30th and Troost.

There also is an increased appetite for revitalizing the avenue between 31st and Linwood.

But it’s such housing-based Troost developments as Milhaus and UC-B Properties’ project at 27th Street, Wonder lofts at 30th Street, and Mac Properties’ four-corner proposal at Armour Boulevard that most directly meet the Troost Coalition’s vision.

“These projects are ready to go. They’re either redoing the building, getting ready to tear it down or putting shovels in the ground,” Simmons said. “It’s very vibrant. They’re truly at places along Troost where you’re not going to take it back. Once it’s there, it anchors.”

Click on the interactive map below to learn more about developments coming to Troost.

From disarray to allies

A little more than five years ago, the neighborhoods of Troost — Longfellow and Hyde Park to the west; Beacon Hill, Center City, Squier Park and Manheim Park on the east — weren’t yet united.

Then came Dollar General.

The discount retailer approached Hyde Park in 2012 about locating a new store along Troost, said Matt Nugent, a founding member of the Troost Coalition and an associate at Gould Evans. When the residents of the Hyde Park neighborhood association declined, the company crossed the street to get a yes from Manheim Park.

“This is a typical pattern … where businesses that wanted to move in would probe for the neighborhood with the least capacity to shape development,” Nugent said. “They’d find a weak point.”

Neighbors found the retail proposal unattractive because of its steel building design and poor aesthetics, Simmons said. Also, it’s parking lot was “twice as big as the building” and wholly unnecessary for a neighborhood where people would be walking to the store, she added.

“It took trench warfare to get the development stopped,” she recalled. “Then someone said, ‘We’re going to do nothing but this — all the way up and down Troost, all the time — if we don’t change what Troost is.”

That meant approaching the city to ask for neighborhood authority over land use and design guidelines, Simmons and Nugent said. They were encouraged to find the city manager and planning department agreeable, as well as willing to help group members get up to speed as they crafted the overlay.

The Troost Coalition’s goals were the same as those of the city’s, planning director Williams explained.

“As planners, we have a role in helping people protect the investments that they’ve made,” he said. “If they’re making an investment on the corridor, they want to know someone who comes along is going to value that investment by meeting higher standards.”

And as the all-volunteer team learned everything it could about planning, development and architecture — with as many as 40 people from all areas of the community gathering twice a week for weeks on end, Simmons said — the city found itself happily less needed in the process.

“Each time we met, our position in the room kept moving further and further to the back,” Williams said. “It’s the community really having a dialogue among themselves. We were initially helping to facilitate, but toward the end, we were just helping to capture and morph into regulatory language.”

The end result? An additional layer of zoning regulations gives the group authority over numerous aspects of the development process, with Troost Coalition members only making decisions by consensus after taking proposals from developers back to their respective neighborhoods.

“From the cities we’ve worked with, the way that the Troost Coalition is structured is one of the best examples of how a high-functioning neighborhood group works,” said Brad Vogelsmeier, director of development at Milhaus, which is constructing 185 apartment units with Kansas City-based UC-B Properties as part of a $24 million project at 27th and Troost.

Having the overlay in place — full of thoughtful detail — helped form the basis for how Milhaus and its partners would design the project, Vogelsmeier said, specifically citing green space and security as areas of top concern for the Troost Coalition.

Such developments’ success truly can hinge on how well they fit into the surrounding communities, Simmons said.

A $120 million residential and retail concept proposed earlier this year for 25th and Troost encountered early opposition from its neighbors who criticized the height and density of the 350-unit project from developers Andrew Brain and Andy Talbert. Though the proposal was later taken to the Troost Coalition for consideration, it hasn’t resurfaced. Talbert confirmed the team no longer is pursuing the project, citing only “difficulty making it pencil in the neighborhood.” A new developer has taken over conceptual plans for the property in some capacity, said John Wood, Neighborhood and Housing Services director for Kansas City, but no proposal has been submitted.

Zipping predatory businesses

“Until this group got to work, pretty much the only businesses or institutions that wanted to come here were all about exploiting poor people,” said Lori Buntin, Simmons’ partner and co-owner at Hoop Dog Studio.

For members of the Troost Coalition, that list includes car washes, payday loan lenders, salvage operations and liquor stores, among others. Such “predatory” businesses feed on the lower-income population and help perpetuate societal problems, like addiction, and the crimes that come with them, Simmons said.

“We get a fair amount of juicers,” she said.” Unlike more middle-class areas where you have better dope, they do a lot of drinking. …. If they’re loud, harassing women, and wanting to sit on the corners or use us for a urinal, we’re pretty strict. I’ve been known to go out with a bucket of soapy water and say, ‘Move or get it!'”

Since relocating to Troost in 2005, the women said they’ve seen mostly property crimes, but acknowledged Kansas City’s crime problems can be different block by block. In mid-August, an 18-year-old college student was killed just a few streets to the south, near Armour and Troost, while out getting an afternoon haircut, according to media reports.

“You can turn a corner and be in a different land,” Simmons said.

Still, people who think Troost is a segregated, crime-ridden ghetto haven’t been down the corridor lately, she said.

“There are at least as many white people as there are black on this street now. And there are people who don’t see it any other way,” Simmons said. “They’re not looking over their shoulders as they walk. … We’re aware of the crime problems, but I don’t think it’s that different from any other urban area.”

Buntin sees the street as a point of connection. One of her art pieces hanging on the walls at Hoop Dog Studio depicts the six Troost Coalition neighborhoods as different fabric designs, united by a long zipper — Troost Avenue — down the center.

To ensure life imitates art, the group circles back to new residents, Nugent said.

“In the Troost neighborhoods anymore, it’s mostly single-family houses. We know we’re missing a big segment of the market where people who can’t afford a full, single-family house also maybe can’t find an apartment, so they move on to somewhere else,” he said. “We’d really like those people to be in our neighborhoods because it would provide a more well-rounded mix of people.”

Business development will follow new tenants, Simmons added.

“When there are enough residents here, in the right buildings, commerce will happen,” she said. “And it will be the right kind of commerce. It will be organic to the needs of the neighborhood.”

It might take years, but skeptics and naysayers soon will see the fruits of the Troost Coalition’s volunteer efforts, Simmons said.

“Troost is bigger than Troost. It’s white, black, poor, medium-income, rich. It’s everything to save Troost,” she said. “Some still have the mindset that Troost is a divider and you have to pick a side. It’s not true. And it’s going to prove itself not true.”

Check out the rest of Startland’s six-part series on new development on Troost Avenue, a historic racial and economic barrier in Kansas City.

Part I: Transforming Troost

Part III: Wonder lofts

Part IV: Back to Troost

Part V: Food startup Village

Part VI: Troost Collective