Feb. 22 update: After a robust, 40-minute conversation Thursday, the full Kansas City Council voted 7-4 to pass a proposed ordinance that would prohibit short-term rentals in residential neighborhoods zoned as R-7.5 and R-10.

Voting yes: council members Scott Wagner, Heather Hall, Dan Fowler, Lee Barnes, Jr., Alissia Canady, Scott Taylor and Kevin McManus. Voting no: council members Quinton Lucas, Jermaine Reed and Katheryn Shields, as well as Mayor Sly James. Not voting: council members Teresa Loar and Jolie Justus.

Of the nearly 800 short-term rentals in Kansas City, Missouri, Steve and Barbara Mitchell might be the only people with a lawful operation, Steve Mitchell said.

Related Stories

• HomeAway, Airbnb critics fearful of strangers in neighborhoods, apathetic landlords

• Tech leaders: City needs more innovative approach to regulating the sharing economy

“For our carriage house, we have what’s called a certificate of legal non-conformance,” said a laughing Mitchell, a real estate attorney with Lathrop Gage and a HomeAway host. “Of the 800 (hosts), we’re probably the only ones that are completely legal in Kansas City right now.”

While the Mitchells’ legal operation puts them in the minority among Airbnb and HomeAway hosts, they’re part of a sizable group fighting against a newly proposed ordinance that’s drawn ire from hosts, neighborhood groups and the area tech industry.

The latest draft — produced from a winding, and at times fiery, three-year process — is Ordinance No. 170771, which the full Kansas City Council is expected to take up on Thursday.

Steve with a certificate of legal non-conformance.

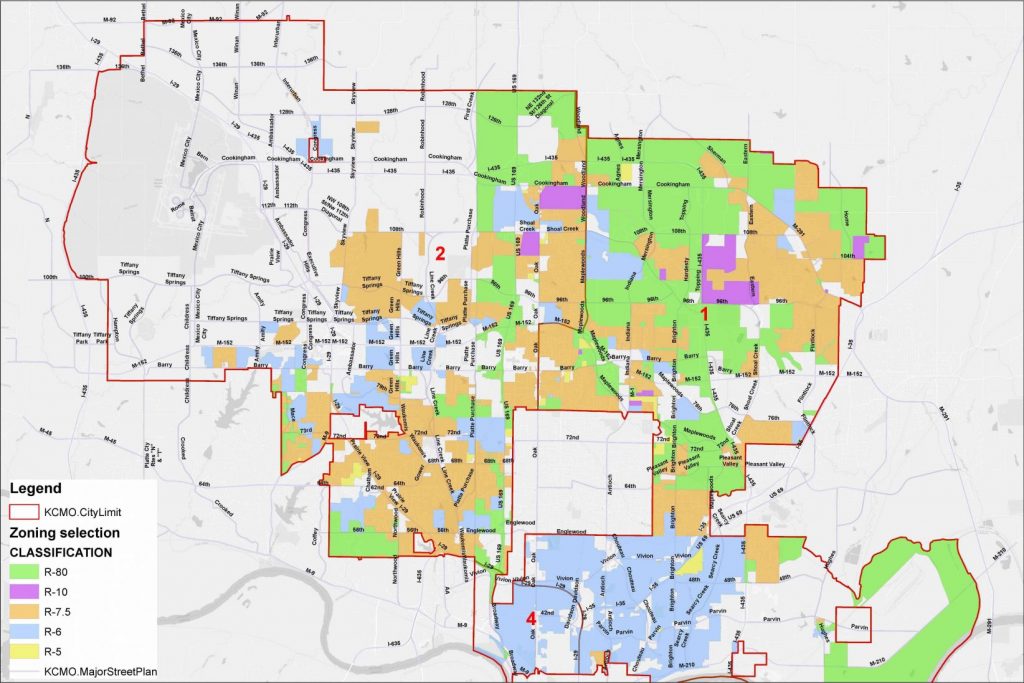

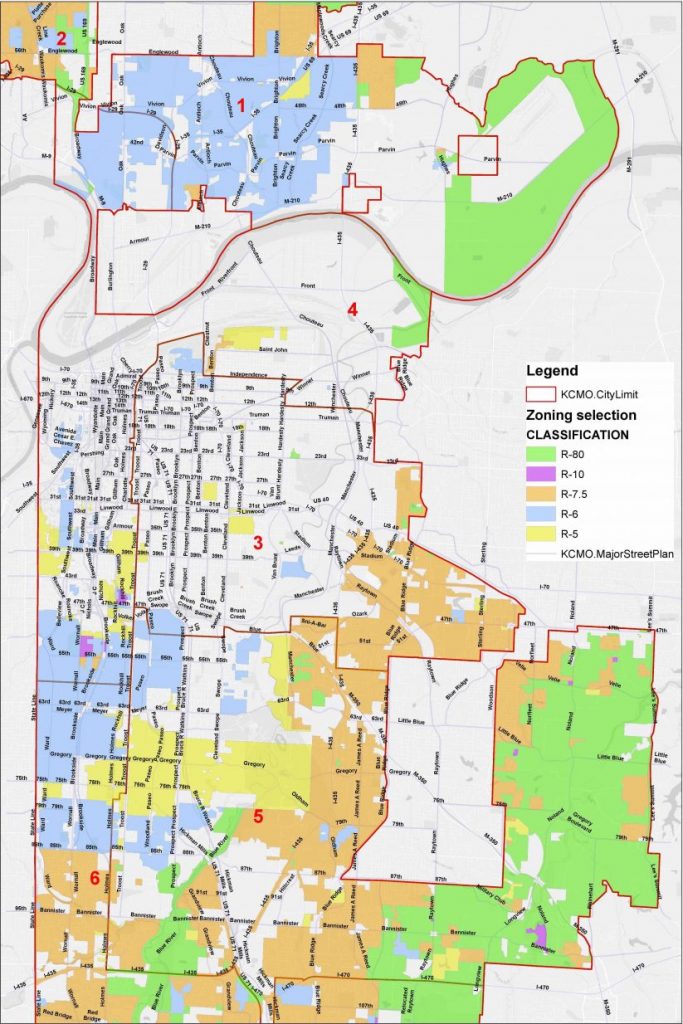

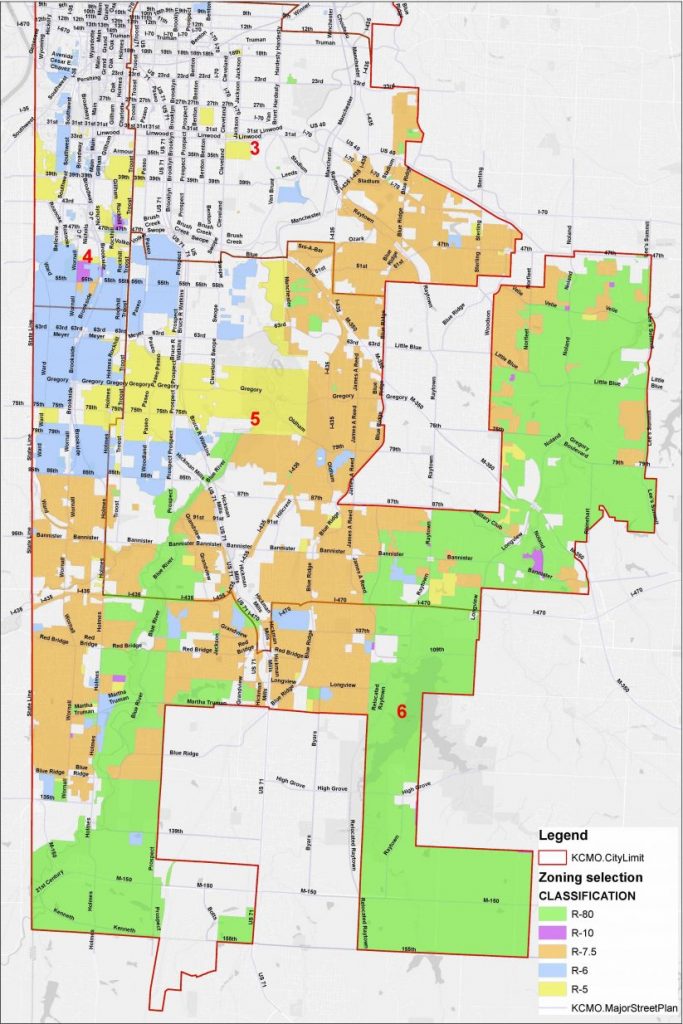

In addition to adding a new fee and permitting structure for hosts, it bans new applicants for short-term rentals in specific residential districts that comprise huge areas in southern and northern Kansas City. Located in mostly suburban areas, the R-7.5 and R-10 single-family districts feature homes on large lots with more than 7,500 square feet of gross site area.

The districts are major portions of Kansas City — and they represent two of the city’s four single-family zoning districts, Mitchell said. The proposed measure was prompted by certain neighbors’ fear of the unknown, he added.

“It’s only because of NIMBY — ‘Not In My Backyard,’” said Mitchell, who’s served as a real estate attorney for 42 years. “It’s people’s concerns that they don’t want strangers living or staying there. They just don’t understand the modern world of searching a platform for housing alternatives.”

A long road to regulate

The proposed ordinance — at least the eighth version since June — is the latest attempt by the city to embrace the sharing economy and legalize nearly 800 properties now listed on Airbnb and HomeAway.

At its core lies an enduring challenge for Kansas City to find harmony between residents’ concerns and disruptive technology, said Diane Binckley, deputy director with city planning and development.

“From the very beginning, we’ve approached this issue as a quest to find the best way to balance the rights of property owners to rent out their homes, and the rights of neighbors to preserve and protect the character of their neighborhoods,” Binckley said. “We want to modernize city regulations to acknowledge the sharing economy. As you know, it’s currently illegal to rent homes for short-term rentals.”

The city set out to rectify short-term rental challenges in 2015, and in that time it’s garnered feedback from hundreds of people, Binckley said. The city has played host to several community meetings, heard personal testimony in multiple public hearings, as well as gathered input online via its virtual town hall at KCMOmentum.org and from the city’s social media accounts.

“We have engaged with many stakeholders, including people who rent out their extra rooms, staff from home-sharing businesses, neighborhood leaders, everyday residents,” she said. “City staff appreciates the involvement of so many residents, neighborhoods and business leaders in this process. It’s a great example of community engagement to create new policy. This is an issue that many cities and states are tackling right now, and we are working to create a solution that works for Kansas City.

“This is the right way to create public policy, by making sure that everyone is involved and has opportunities to make their concerns and opinions known, and to make sure that input is written into the policy,” she said.

What’s in the measure?

That community engagement has coalesced into the Ordinance No. 170771, she said.

The measure bans new short-term rentals in the R-7.5 and R-10 single-family districts but grandfathers in current short-term rental operations. Historic districts and historic landmarks in the districts are exempt and have the option to offer short-term rentals.

If passed, the ordinance would create new fees and permitting requirements. All short-term rental hosts must get a permit, and there are two types of permits: owner-occupied (Type 1) and non-owner occupied (Type 2).

Administrative approval for all hosts costs $259, while a $596 special use permit is required for all hosts in historic areas or those grandfathered in a banned district. First-year registration costs $275 and subsequent annual registration costs $175.

A band of roughly 50 short-term rental hosts aren’t as concerned with the fees as they are with the banning of the two residential districts, Steve Mitchell said.

Such a ban is legally flawed, Mitchell said.

The Mitchells with their short-term rental

“There’s no good reason not to treat those districts are same as other districts. … They tried to split the baby illegally,” he said, noting that about 150 people operate short-term rentals in the R-7.5 and R-10 districts. “I think what they’ve said is ‘We’ll grandfather the people that have been illegally doing it, but we’re going to prohibit all you people that have stood by and legally not done (short-term rentals). … It doesn’t fly under Missouri Voting Law that you can prohibit something that’s otherwise being allowed in all zoning districts except these two just because there are sure a few people that don’t want it in their backyard.

“There’s really no good reason against (short-term rentals) — other than ‘We don’t like change.’ I think they’re sincere but they just don’t understand the modern sharing economy and think that some of them think the Ramada Inn is going to go up next to them. … This helps so many people with paying their mortgage and their upkeep,” he added.

The impact of sharing

In 2017, more than 75,240 people booked Airbnb rentals in Kansas City, according to the San Francisco tech giant. As a result, Kansas City hosts raked in about $7.7 million in income.

In total, Missouri host community earned a combined $28.8 million in supplemental income while welcoming about 289,000 guests to the state in 2017.

Kansas Citians stand to lose more than just direct income, said Ryan Weber, president of the KC Tech Council. It reflects poorly on Kansas City’s reputation as a burgeoning Midwest tech hub when it’s unable to accommodate tech platforms like Airbnb and HomeAway, which could hurt its prospects to attract talent and companies, he said.

“This will be a PR nightmare for Kansas City,” said Weber, whose organization represents the area tech industry. “Once again, council chose to regulate the sharing economy rather than embracing technology that’s finding its way into the city.”

The short-term rental situation has drawn comparisons to the city’s challenges to craft regulations for the ride-hailing firms Uber and Lyft.

The city initially drafted for-hire transportation regulations that compelled Uber to temporarily leave the city, sparking a heated response from area business leaders. After its own negotiations fell apart, Lyft departed the city for nearly three years but eventually returned in July.

Ultimately, the city needs to hear out those who are moving the community forward, said Elizabeth Herder, a nonprofit consultant and Airbnb host in southern Kansas City.

“They should be catering to the wealth creators in Kansas City in this decision,” she said. “But that’s you and me. That’s those of us in the prime of our professions — we’re having families, we’re spending money. We aren’t settling in, and kicking back. We’ve got decades of voting and spending money in Kansas City ahead of us.”

For more in this short-term rental series, click here for a piece on neighborhood reaction to the ordinance and here for the tech industry’s perspective.