No turning back now, Ilan Salzberg said.

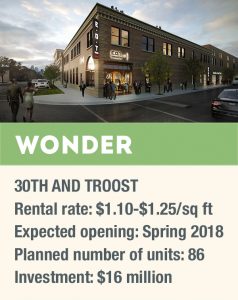

“This is real,” the Wonder lofts developer laughed, gesturing at the freshly installed kitchen cabinetry and hardware in a model apartment unit at 30th Street and Troost Avenue.

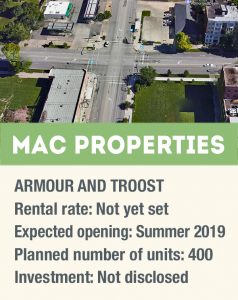

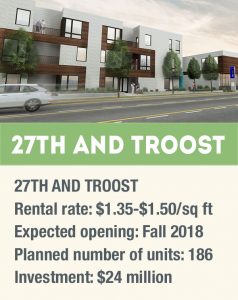

Wonder is expected to be the first of three major residential developments to open between 27th Street and Armour Boulevard along Troost — together bringing about 670 new housing units to the corridor — which has a checkered racial history and suffers from the stigma of high crime.

Set in a former Wonder Bread bakery, plans for the 30th Street project marry about 86 apartments in the historic space with a first-floor brewpub, commercial space, and a rooftop deck for events and entertaining, said Denver-based Salzberg and his local partner, Caleb Buland of Exact Architects.

The apartments are expected to welcome their first tenants in the second quarter of 2018, Salzberg said.

Wonder’s trajectory is proof the often-maligned street is beginning to “pop,” said Scott Burnett, chairman of the Jackson County Legislature and whose district includes the corridor.

“Troost has been the dividing line between black and white, and most people think of it as a scary place that they don’t want to come to,” Burnett said. “And that’s slowly changing. The bakery building will make an enormous difference.”

Opportunity to share access, resources

Bringing new residents and activity to Troost, of course, isn’t without controversy.

“From my perspective, anytime an old building has new life, it’s a wonderful thing. But then there’s a lot of dynamics to that. Where there comes change, there comes fear,” said Sheryl Vickers, owner of Select Sites.

Vickers worked as a tenant representative for Chris Goode, connecting the Ruby Jean’s Juicery owner with Salzberg and Buland, who then partnered with Goode to bring the popular business to a street corner across from the Wonder lofts complex. Ruby Jean’s Kitchen and Juicery is expected to open Nov. 11.

Both sides win when developers take the existing stakeholders — residents and businesses — into account when making plans for a corridor like Troost, Vickers said.

“I feel like one of the answers is creating true 50-50 partnerships with a person or group from the neighborhood, so it takes away the concern that you’re coming in with your own ideas and enforcing them. It’s clear that it’s a collaborative effort,” she said.

Another avenue for development to benefit the surrounding community should soon be seen with the Heart of the City Neighborhood Stabilization TIF, said Dan Moye, development services specialist at the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City. The TIF district runs south on Troost from 27th Street to Emanuel Cleaver Boulevard, a half block on either side, he said.

“It’s goal is to capture some city earnings tax revenue from the new Kansas City Public Schools headquarters building (at 29th and Troost), and reinvest that in the immediate neighborhood,” Moye said.

Money could be dispensed as early as later this year for single-family home rehabilitation, back funding for new home construction, grants, loans, and infrastructure improvements, he said.

“Our hope is to be able to address 10 to 15 homes a year. Obviously that’s not a huge amount, but the hope is to become a catalytic fund,” Moye said. “As more people are able to fix up their homes, that snowballs and gets more people invested in the area.”

Ryan S. Harvey, Abundant Thinkers

Residents across Kansas City’s east side — not just along Troost — would welcome such outreach efforts, said Ryan S. Harvey, a speaker/consultant with Abundant Thinkers, volunteer educator and east side native. For too long, access to greater opportunities has felt out of reach, he said.

“How can communities be this close, and a street dictates what is accessible?” Harvey asked. “Things magically become better on the west side.”

It’s not lost on east side residents that Troost is seeing revitalization at the hands of white developers investing in largely black neighborhoods, he said. Some people are skeptical of their motives and promises, Harvey said. Others are worried. Even angry. But he acknowledged longtime residents of the area typically lack the access to resources to initiate such projects themselves.

Check out the rest of Startland’s six-part series on new development on Troost Avenue, a historic racial and economic barrier in Kansas City.

Part II: Troost Coalition

Part III: Wonder lofts

Part IV: Back to Troost

Part V: Food startup Village

Part VI: Troost Collective

“It feels like we get rations,” Harvey said. “The system is cruel.”

Growing up without access to resources breeds a sense of hopelessness, he said. For many, that feeling ultimately translates into insurmountable pain and discouragement, followed by the higher crime rate that has given the east side and Troost a bad name, Harvey said.

“If you have to travel a certain amount of miles to get groceries, that does a certain amount of damage to your psyche. You start to not want to eat as much or as well. If you have to travel far to go to work, if you don’t have access to money to buy a car, you’re deterred from getting a job. You might give up,” he said. “There are just so many ways you might be deterred from actually trying because your life is already so uncomfortable. So you’re going to go out of your way to find the smallest bit of happiness, of comfort.”

And then there’s the anger — anger at seeing opportunity or material desires just out of reach or in someone else’s hands, he said.

“It can either motivate you or make you so pissed you’ll do anything for it,” explained Harvey, who said he lost an older brother, close friend and uncle to violence. “That’s the scary thing. Too many people will do anything. Not the right thing. Anything.”

Kansas City’s east side is rich with many great residents, he emphasized, but the challenges of poverty are overwhelming.

“The worst thing is the mindset that someone else has to let us out of this, that we can’t do it ourselves,” he added.

The road to division

Troost’s racial divide isn’t rooted in ancient history, Jacob Wagner said. It’s a product of a dramatic shift in population and economy — some of which happened only in the past 50 years.

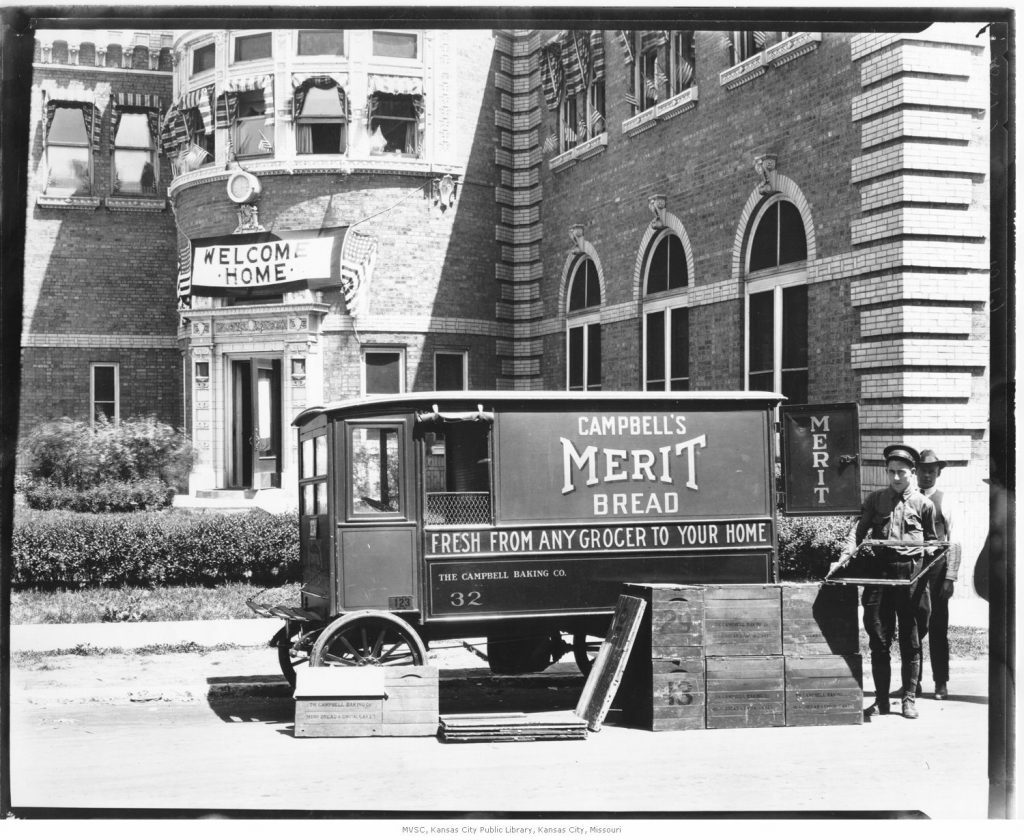

“31st and Troost was one of the first major commercial shopping districts outside of downtown. Back in the day, it used to be really busy,” said Wagner, associate professor of Urban Planning and Design at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “There were hundreds of businesses, thousands of residents. It was definitely a neighborhood center for all the neighborhoods around there. It was a vibrant place.”

Though the underlying racial tensions of the day were present, Troost still boasted a cross-section of ethnicities, with the corridor even serving as the heart of Kansas City’s Jewish community.

So what happened?

It began with Kansas City development icon J.C. Nichols and others pushing the growth of the city south and west, away from its natural path eastward, said John Hoffman, co-managing partner for UC-B Properties, which is developing a 186-unit apartment project at 27th and Troost.

“In the old days — the 1880s to the early 20th Century — Kansas City was growing toward Independence,” Hoffman said, noting Independence was the county seat and center of local government.

Nichols was successful at developing the Country Club Plaza, which kept momentum moving toward Crestwood, Brookside and Prairie Village, Hoffman said.

“That was the end of development east,” he said.

In addition, the government began picking winners and losers at the geographic level through a process called “redlining,” said Jackson County’s Burnett. In Kansas City, one of the separation lines was at Troost, making it more difficult for those on the east side to get loans to build or even maintain their homes and businesses, he said.

“You had massive white flight after World War II,” Wagner further explained. “The federal government put in a ton of resources to subsidize single-family home purchases for the development of post-World War II suburbs. That was a racially biased process. African American homeowners didn’t have the same access to mortgages and loans, so they weren’t able to afford to move out to the suburbs in the same way that millions of white working class and middle class were.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education ruling, which desegregated schools, also fueled white flight to the suburbs, Hoffman said, noting the newly built federal highway system made it easier for people get around the urban cores they were fleeing.

For Troost, another dramatic hit came in 1968 when riots scorched Kansas City’s east side in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Violence erupted after initial peaceful protests were met with tear gas from the police, according to the Kansas City Public Library.

“Black protesters proceeded to vandalize and burn white-owned businesses. Within two days, a three-block-wide section of town running down Prospect Avenue lay in ruins. Over 1,700 National Guard troops joined 700 policemen in putting down the riot. For two nights, bullets flew from both parties as police and firemen battled to maintain order and put out fires,” according to the library. “Nearly 300 arrests were made, mostly of young black males. Tragically, seven black citizens died in the violence.”

News coverage of the riots — in the still relatively early days of broadcast television — left a mark on white America, Wagner said.

“It really impacted people’s perception of racial issues in Kansas City and it fueled that racial shift from mixed neighborhoods to predominantly white neighborhoods west of Troost and black neighborhoods east of Troost,” he said.

In the years since, a predictable pattern emerged: Many of the remaining property owners clung to the past without the resources to plan for the future, said Cathryn Simmons, a member of the Troost Coalition who lives and works on the corridor.

“People who owned buildings just rode them out because nobody else wanted them, then they decayed and they just knocked them down,” she said.

Others continue hanging onto properties — maintaining them just well enough to prevent total collapse — in hopes of a big payday when a developer finally comes calling, Simmons said.

“They say they’re saving them, but they’re not really fixing them up,” she said. “The buildings are falling in.“

Click on the interactive map below to learn more about developments coming to Troost.

Troost transformation

Make no mistake: Developers, neighborhood leaders and city planners are indeed hoping to change the face of Troost.

Not from black to white, they say, but from stagnant to vibrant.

“The idea is not to see improvement happen on the corridor at the expense of making somebody feel that they’ve been pushed off the corridor, not welcome on the corridor,” said Jeffrey Williams, planning director for Kansas City. “There’s a real opportunity to create this really great, diverse, eclectic, welcoming community for a wide range of people with a wide range of socio-economics.”

For Wonder, that means taking the local community’s needs into account when developing the commercial space on the project’s first floor, Salzberg and Buland said. Expectations for services in a person’s “third space” — a place that isn’t home or work — can vary wildly between Colorado and Troost, Salzberg acknowledged.

“As a Denver white kid, I want my kombucha and my Wi-Fi; that’s just what I expect,” he said. “If you’re a black guy who grew up in Kansas City, that’s not necessarily on the list of what you’re looking for.”

Large, arched windows that open to the street will allow sunlight to fall onto an open arcade area in front of Wonder’s brewpub and shops, but determining exactly what that sunshine illuminates remains in the works, Salzberg said.

“White guys in beards like to hang out in breweries. OK. Fine. Everybody likes beer to some extent. But we want to try to figure out the retail needs that will actually bring a variety of people here, so that we have that beautiful mix,” he said.

A bigger part of the inclusion equation is whether existing residents will be displaced by what some call the “gentrification” of the Troost corridor, Wagner said.

“If Ilan Salzberg or Exact (Architects) pick up a building that never had any housing in it, and they add units where there wasn’t, they’re not displacing anybody directly,” he said, noting the transition of the long-vacant commercial bakery to residential housing. “But if then other developers see the value of the land around them differently because this guy from Denver comes in and develops a bunch of lofts, they might then raise their rent, which might impact other tenants.”

The city’s planning department has been intentional about working to ensure equitable development along Troost, Williams said. That means redevelopment efforts need to benefit the entire community, he said.

“It’s really about understanding what we’re doing from a social place-making perspective,” Williams said. “These are great environments where we really can offer a high quality of life for people at a variety of price points.”

To reach that higher standard, Troost first needs to be stabilized to provide long-term opportunities for new and existing residents and investors, he said.

People must be willing to take a risk to break Troost’s destructive cycle of doubt and decay with a constructive approach to community building, Wonder lofts’ Buland said.

“Not only are these are single biggest assets — our homes and our businesses — but it’s also the thing that shapes our daily experience,” Buland said of transforming life on Troost. “It’s going to take a village. It’s going to be an initiative up and down this district. And what we hope is that it’s a grassroots thing. We want the people who live here, as well as us who work here, to all lift it together.”

Check out the rest of Startland’s six-part series on new development on Troost Avenue, a historic racial and economic barrier in Kansas City.

Part II: Troost Coalition

Part III: Wonder lofts

Part IV: Back to Troost

Part V: Food startup Village

Part VI: Troost Collective