A lot can go wrong when flying a drone around a high-rise building, acknowledged Andrew Patch. Think restricted airspace, pigeons, hawks, turbulence, swirling winds, pressure changes, trees, powerlines, and other unexpected obstacles.

But behind the sticks of a controller, Patch steers into the challenge.

In February 2017, he founded Heartland Drone Company, an Federal Aviation Administration-certified aerial imaging company specializing in real estate, creative projects, and now, building inspections. Last October, after an uptick in business, he launched a spinoff, PropTechHD, to apply drones for engineering supervision, facade and roof inspection, and other tasks needed for monitoring commercial building safety.

“Instead of having to touch the side of a building up close or having to walk a large rooftop, we can now scan it with a drone and see every square inch,” Patch said.

The traditional way to inspect a building requires ladders, swing stages, hoists, and ropes — all of which is time consuming, expensive, and risky, he said. But through drone technology, Patch can reach parts of buildings that are inaccessible and produce detailed images that are far more thorough than the naked eye.

In June 2021, after the partial collapse of a condo building in Surfside, Florida, business spiked for the venture that would become PropTechHD. As a result, Patch received more requests from condo associations needing help inspecting balconies, facade systems, and the status of their buildings’ safety.

“That was a major inflection point across the entire commercial building ecosystem, not just in the United States, but globally,” he said.

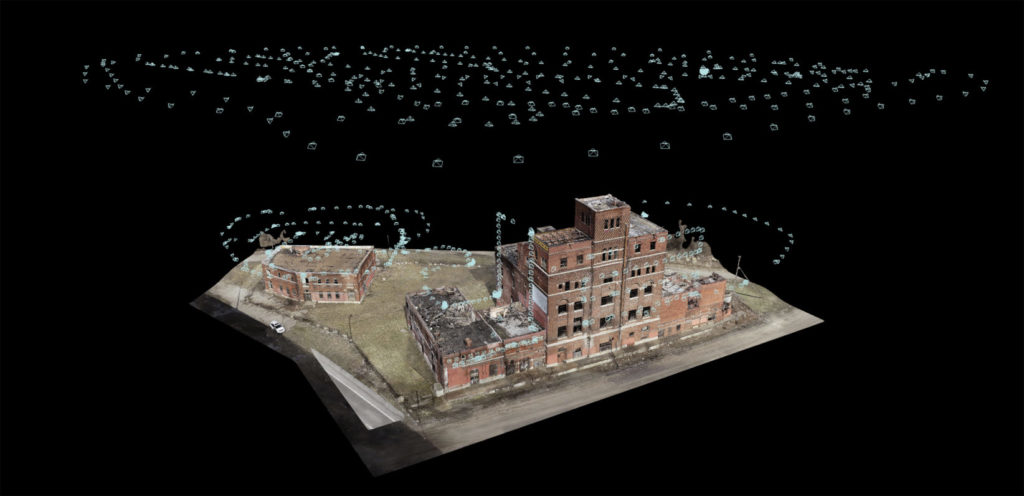

Drone-generated 3D model of a building exterior; image courtesy of PropTechHD

Some of the bleeding-edge technology available to drones includes thermal censoring and 3D terrestrial scanning with lidar, and recently, Patch has been flying inside buildings for interior reality capture with laser scanning. It’s now possible to generate a 3D model of the exterior and interior of a building that can exist digitally, he said.

The possibilities are emerging and endless, Patch said.

“The drone industry can be defined as paralysis by analysis,” he said. “There’s so many things you can do with drones, it can be difficult to know which rabbit hole you want to go down and build a business out of. I went down a lot of different rabbit holes.”

Because Kansas City has both urban and rural environments, his type of work remains lucrative. One day he’s flying around skyscrapers, the next day he’s in the middle of a cornfield aerial mapping 150 acres for a new housing development site.

“We really have an exciting mix of different industries so it creates a very diverse workload for me,” he said.

In his early entrepreneurial years, Patch explored many interests, from football and exercise science to graphic design and videography. He discovered drones as a solution for capturing better photos and videos for his clients, who were mostly friends and family to start. The hobby turned into a freelance opportunity, which later became Heartland Drone Company.

Clients have included Facebook, his alma mater, Baker University, the Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

One day in 2021, he received a cold call from an engineer asking if Heartland Drone Company provides building inspection services. In the spirit of figuring things out, Patch agreed to the project though it contained many unknowns. The opportunity resulted in his introduction to using drones beyond marketing and real estate applications.

Ultimately, Patch flew a drone around an 18-story building in downtown Kansas City to capture high-definition photos of the facade for his new client, STRATA Architecture + Preservation, with whom he still works today.

“They were like, ‘These images are stunning,’” he said. “‘They’re high definition, we can zoom in on them, we can see cracks, we can see organic growth, we can see decay. There’s so much we can gain from this.’”

As Patch dives deeper into such work, he’s learning that each client — property managers, engineers, commercial roofers, and building owners — has a wide range of needs. Some want data to fix issues before they arise, while others want precise measurements to estimate the cost of building materials.

In every scenario, Patch’s main challenge is confronting traditions and educating clients on how they can use drones as tools to collect information to meet those differing needs.

“Because we’re working in these spaces where it takes a lot of education, players are starting to be more accepting of the technology and what it can actually do,” he said.