Editor’s note: The following is the second in a series of analyses of Startland’s list of Kansas City’s Top Venture Capital-Backed Companies.

On stage with a handful of men, Erin Papworth faced a dilemma.

The founder of Nav.It — one of the startups to recently complete Fountain City Fintech’s second accelerator cohort — found herself fighting for speaking time earlier this fall during a panel with just one woman among the spotlighted guests.

“I realized probably halfway through that the guys on this panel were jumping really quickly at answering all the questions,” Papworth said. “It was awesome in a way; they all made sense and were articulate. Great for them, but I’m going to have to fight to get my voice heard in that, right?”

The moderator — a man with good intentions, she said — had given the panelists ground rules for speaking; guidelines intended to limit the amount of time spent by the whole panel on each question by discouraging cross-talk and interruptions.

“As the only woman on the panel of five dudes, talking to a majority male audience, there is a question that I have in mind: ‘OK. If I assert myself, I could be perceived as bitchy or overbearing. And if I don’t say my peace, then I’m just being run over,’” Papworth said.

Ultimately, she decided to share her perspective — and try to prove that her addition to the conversation was twice as valuable as the contributions of her male counterparts on the panel, Papworth said.

“As a female founder, we have to be better than our competition,” she said, drawing a parallel between the event and the daily process of building a startup in a male-dominated space like fintech. “You have to be tough. You have to make sure your business is incredibly sound. Nobody is going to give me $5 million on just a good idea, which is what some other founders historically have gotten.”

Investment inequity

Papworth’s company, Nav.it — a money management app made by women to help a largely female user base be more financially confident — experiences many of the same challenges as male-run startups, she said.

“The double-edged sword of it is that I am a female founder with a female-forward fintech app,” Papworth said. “So on multiple levels, I’m trying to educate people about why women are important as a market.”

[pullquote]The Top Venture Capital-Backed Companies List recognizes the momentum pushing an emerging cohort of Kansas City growth-stage, venture-backed companies. Click here to check out the full list.

[/pullquote]“I’m not asking anyone to lose money,” she continued, discussing how women can be subject to different expectations, assumptions and scrutiny. “We’re all in the game here to build meaningful and sustainable companies that do the right thing for our customers and investors.”

While Seattle-based Nav.it hasn’t struggled as much as some women-led startups seeking venture funding, she said, Startland News’ 2019 list of Top Venture Capital-Backed Companies suggests many local firms aren’t so fortunate.

Of the 61 companies on the list with at least $1 million in funding, only 12.2 percent of the 115 founders and co-founders were women. Similarly, only 12.2 percent of those leaders were non-white.

Click here to check out the list of Top VC-Backed Companies.

Click here to read about how Kansas City’s Top-VC Backed Companies are reshaping the startup landscape.

Is there a bias in favor of white men in tech?

Gender and race are frequent topics in startup and investment circles, Lisa Tamayo admitted.

“I’ve had to learn to be just the CEO,” the co-founder and CEO of Scollar said. “People ask me, ‘What’s it like to be a female CEO?’ And I say, ‘I wouldn’t know. I’m just the CEO. My job is to keep things moving.’ So I’ve had to degender myself to be effective.”

While women and minority founders often feel like they have less influence than their white male counterparts, Tamayo said, she found strength in the power she and her startup — a smart pet collar that recently relocated from the West Coast to Kansas City — bring to the table.

“I’ve been chewed up and spit out more than once by investors. I’ve now gotten to the point where I walk in realizing that I am the prize and they need me. That switched how I think about it,” Tamayo said. “There’s probably a rich opportunity for a minority founder — whether that’s a woman or a person of color, male or female — to step into those investor meetings and recognize their identity does not put them at a disadvantage.”

But not every founder has access to those meetings — or even the pathways to them, said Sam Hasty, managing partner for OHUB.KC.

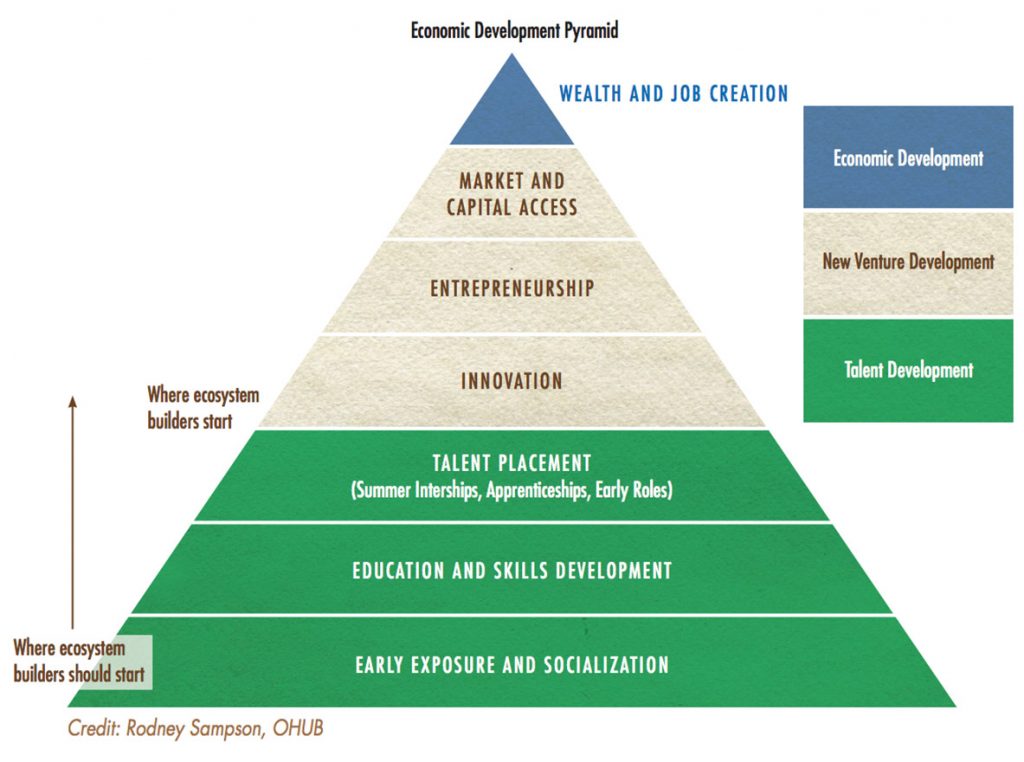

Citing an Economic Development Pyramid detailed in the Inclusive Ecosystem Guide — prepared in concert between the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Dell Gines and Opportunity Hub founder Rodney Sampson — a foundational understanding of entrepreneurism is required to succeed, Hasty said.

“At the bottom of the pyramid is early exposure and socialization. Because of generational and systemic oppression in this country, that early exposure and socialization has not been accessible to communities of color,” he said.

Click here to check out the full Inclusive Ecosystem Guide.

Hasty, whose parents were both entrepreneurs (one in finance), had opportunities that aren’t universally shared by potential women and minority founders, he said.

“Growing up, around the breakfast table, I’m hearing about debt and equity. That’s not always the case — not all people are afforded that luxury, regardless of their race, color or creed,” he said. “But it’s particularly pronounced in communities that have been intentionally boxed out of these positions in finance or that control the checkbooks.”

Click here to read more about how Opportunity Hub, through OHUB.KC, works to broaden the funnel for entrepreneurs.

“New venture-backable founder formation and simultaneous capital capital formation must be precedence; and an intentional focus on racial equity is important to move the needle,” said OHUB’s Sampson. “Ecosystems must move beyond the self-awarding platitudes of achieving one black or one Latinx founder in each and every cohort. This is not the path to equity.”

Opening eyes, access

Kansas City must open its eyes to access issues and a weak support system for minority founders, said Donald Hawkins, co-founder of the found-focused KC Collective.

“A primary focus for me is looking at how we support the ecosystem and cool things that are going on here, but recognize that we somehow seem to turn a blind eye toward the extreme lack of minority founders. How is that not a topic?” said Hawkins, who also is founder of Griffin Technologies, another member of the recent Fountain City Fintech cohort. “Sometimes it gets hidden behind a lack of women founders, but we’re in a city with a lot of black folks, a lot of Latin folks, and it’s never really a topic that seems to come out. I don’t know if people are afraid to discuss it.”

With few examples to cite of minority founders who have succeeded, it’s even more difficult to inspire a next wave of innovation from within underserved communities, he added.

“For minorities, a lot of what we do is based on what we see,” Hawkins said. “And there are a lot of people who are disenfranchised — underrepresented people there in Kansas City who have no clue what it’s like to be involved in venture.”

Papworth agreed founder support within an ecosystem is critical, she said, emphasizing a platform or network that can coach early stage companies.

“I probably wasted a year of my business because I didn’t understand how this whole system worked. It took me a long time, but I don’t feel bad about it; I learned everything I needed to learn,” she said. “But if I had someone to kind of hold my hand and say ‘Look, these are the things you need to have before you go out and start to raise money,’ or ‘You really need to think about your business model,’ then that would’ve just launched me faster.”

Click here to read more advice from female founders stressing the importance of mentors and advisors.

“As an outsider coming in, everyone in Kansas City seems to be really interested in helping everyone else out,” Tamayo said with optimism. “That’s something we don’t see very much in the San Francisco Bay Area — where everyone’s out for themselves. It makes it really difficult to feel that ecosystem and that network. In Kansas City, the animal health corridor [and the collaboration within] makes the environment so fertile for us. It’s been a surprise and a delight.”

This story is possible thanks to support from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a private, nonpartisan foundation that works together with communities in education and entrepreneurship to create uncommon solutions and empower people to shape their futures and be successful.

For more information, visit www.kauffman.org and connect at www.twitter.com/kauffmanfdn and www.facebook.com/kauffmanfdn