A high-speed Missouri Hyperloop route connecting Kansas City and St. Louis would power a state-spanning metro area with fluid access to tech jobs and talent, as well as a region pumped for economic growth, leaders familiar with the proposed project said.

“You could easily live in St. Louis and work in Kansas City, and have a 30-minute commute each way. That would be better than if you were currently living on the south side of Kansas City and just going to the north side in Kansas,” said Drew Thompson, project lead on the Missouri Hyperloop study released this week.

[pullquote]

Think of the Hyperloop system as high-speed rail travel in a vacuum. Levitated pods are propelled at speeds reaching 640 miles per hour by electric motors through a series of interconnected tubes that create a low-pressure environment, allowing the pods to glide with limited friction at speeds that surpass air travel.

[/pullquote]The independent report, which confirmed the feasibility of a Kansas City-to-St. Louis route, comes a year after the Missouri Hyperloop Coalition announced it would continue studying a supersonic alternative to I-70 with Virgin Hyperloop One. Overland Park-based Black & Veatch — where Thompson serves as director of data center/mission critical facility solutions — led the effort.

“The Hyperloop project would be an international game changer for the state of Missouri,” said Greg Kratofil, chair of the Technology Transaction and Data Privacy Practice at KC-based Polsinelli law firm. “This is one of those generational projects that will draw talented technology people from across the world to Kansas City and St. Louis. Connecting Kansas City’s and St. Louis’ workforces, companies, and opportunities looks like a 1+1=3 for the region.”

Kansas City — like much of the country — currently is in the midst of a tech talent shortage, according to data from the KC Tech Council, of which Polsinelli is a key sponsor and stakeholder. A 2018 KC Tech Specs report indicated 3,000 jobs went unfilled in the previous year — a trend that projects like the Missouri Hyperloop could help reverse, said Thompson.

“It would take quite a few engineers and construction to design this and get it constructed,” he said. “Obviously Virgin Hyperloop One would be providing technology, but the actual design of this for 240 miles — the distance between Kansas City and St. Louis — would require a lot of engineering expertise.”

Affirmation of a hyperloop route’s viability indicates the potential for an economic development ripple effect through not only regional transportation, but also real estate and tourism, tech expert Kratofil said.

Its impact can’t be understated, agreed Drew Solomon.

“The economic benefit could be immense as citizens can work in either community and enjoy leisure activities in both cities, all within a 30-minute or less Hyperloop ride,” said Solomon, senior vice president of business and job development for the Economic Development Corporation of Kansas City. “Imagine working at Cerner and leaving work at 5 p.m. and making a Cardinals game in St. Louis by a 6:30 p.m. first pitch. It would really open up what is possible for people to achieve and enjoy in a day.”

A ‘huge advantage’ for Missouri

The Black & Veatch-authored feasibility study combined the expertise of the top minds at the Kansas City-area global infrastructure solutions company, said Thompson, tapping their industry-leading knowledge of electric vehicle charging setups, wireless communications, pump stations and portals that require high voltage power, and advanced construction materials and techniques.

“It’s been exciting to be part of this project because it’s allowed for the engineers and the people working on this to bring so many of our different disciplines into a single project and a single study,” he said.

Among the Hyperloop report’s key findings, as highlighted by Virgin Hyperloop One:

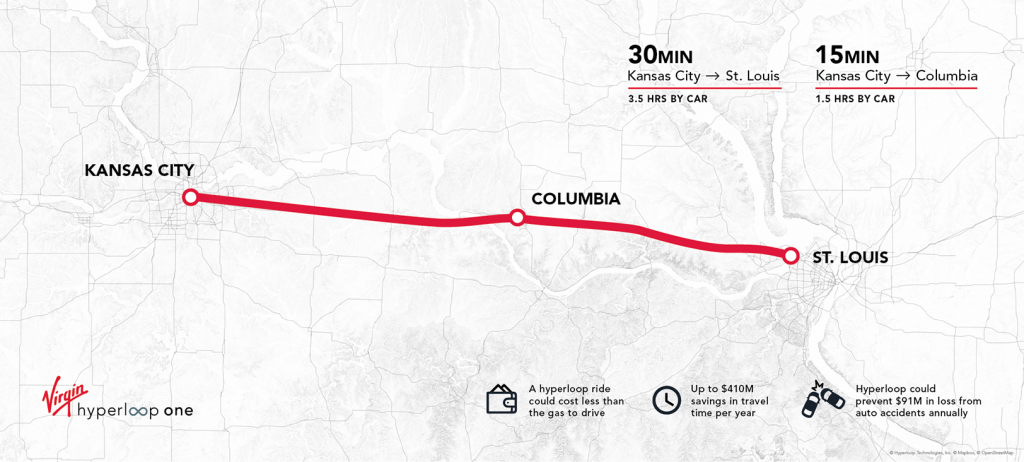

- 80-percent increase in KC-to-St. Louis round trip traveler demand, from 16,000 to 51,000 riders per round trip;

- Savings from less time spent on the road, adding up to $410 million per year in reclaimed productivity;

- Reduction in wrecks along I-70, putting up to $91 million per year back in people’s pockets;

- Travel time between Kansas City and St. Louis could be as little as 28 minutes, compared to 3.5 hours today, and travel time for trips from either Kansas City or St. Louis to Columbia could be 15 minutes, compared to nearly 2 hours;

- The cost to take a Hyperloop from St. Louis to Kansas City could be lower than the cost to drive (based on gas alone), while still cutting down the time by three hours; and

- The study confirms that Virgin Hyperloop One’s linear infrastructure costs are about 40 percent lower than those seen in high-speed rail projects around the world, while the system delivers speeds that are two to three times faster.

The regional geography along I-70 was a significant plus for the proposed Missouri Hyperloop, Thompson noted.

“We looked at a variety of routes: Highway 50, the Katy Trail, I-70,” he said. “[The chosen route] has a wide right-of-way — in fact, the Missouri Department of Transportation owns the whole right-of-way from St. Louis to Kansas City through Columbia. One of the biggest challenges in doing new infrastructure projects in the U.S. today is acquiring right-of-way to use the land and also the regulatory hurdles that different jurisdictional authorities put on you.”

“The fact that this is one piece of land that is fairly flat, fairly straight, and controlled by one entity was a huge advantage,” Thompson added.

While I-70 route isn’t a perfectly smooth or unbending stretch through Missouri, a potential Hyperloop setup could be adapted to fit its features, he said.

“With Hyperloop — when you’re traveling at airplane speeds — you cannot have lots of movement up and down, or side to side, otherwise you have the ‘rollercoaster effect,’ which is not what you want,” Thompson said, noting the proposed route would weave its way around obstacles along the existing I-70 roadway. “[The path] moves to try to straighten out the curves, and up and down to try to straighten out the hills and the valleys. There will be spans where it will cross the interstate and there will be spans where it will cross the overpasses, keeping it as flat and straight as we can.”

Photo by Hyperloop One

What’s the next step?

The fate of the proposed Kansas City-to-St. Louis route ultimately rests in the hands of Virgin Hyperloop One, government regulators and the Missouri Hyperloop Coalition, a group that includes the KC Tech Council, MDOT, the St. Louis Regional Chamber, the University of Missouri System and the Missouri Innovation Center in Columbia, Thompson said.

“My hope — and the objective of doing this feasibility study — is to allow the conversation to progress past, ‘Yeah, I see this could happen. There’s a technology out there, and I-70 looks pretty good, but would it really work?’” he said.

Two other states are currently studying Hyperloop through in-depth feasibility studies — Ohio and Colorado. In addition, Ohio is also participating in the first U.S. Environmental Impact Studies of a Hyperloop system and Texas has announced its intent to start the process.

“Because no one’s ever done it before, I think there’d have to be some regulatory discussion before it could actually be implemented,” Thompson said of the Missouri Hyperloop. “The next step could be developing a 10- to 15-mile route, leveraging what Hyperloop One already knows, which would allow people to test, to do a proof of concept.”

Hyperloop usage would begin as passenger travel, he said, noting freight transportation wouldn’t be economical until multiple routes — like those in Ohio, Colorado and Texas — were built and functional.

“If you start to connect some of those, our ability to move freight at a quick, more-reasonable, much-safer pace with less wear and tear on the highways increases, and it starts to become pretty compelling,” Thompson said.

The opportunities presented by the Hyperloop proposal are too substantial to pass up, said the EDCKC’s Solomon.

“It will take time and an immense public/private partnership, but these are exactly the types of progressive and innovative projects that our state and our major cities in Missouri should be striving for,” he said, also applauding the Missouri Hyperloop Coalition’s efforts so far.

But even economic development leaders and engineers studying the project can’t know the full scale of Hyperloop’s potential, Thompson added, suggesting for example that portals for travelers arriving and departing the transportation system could become mini hubs of business activity. Placement near popular sports complexes and shipping yards could further boost development, he said.

Looking at the cost savings and quality of life upgrades indicated by the study, Thompson hopes Hyperloop talks continue shooting forward, he said.

“At some point, someone said, ’Should we really do a railroad that goes across the country?’ And at some point, somebody said, ‘Should we really do four-lane highways to make it quicker, easier and safer to travel?’” Thompson said. “We need a starting point. Missouri would be a good one.”